Anna Atkins

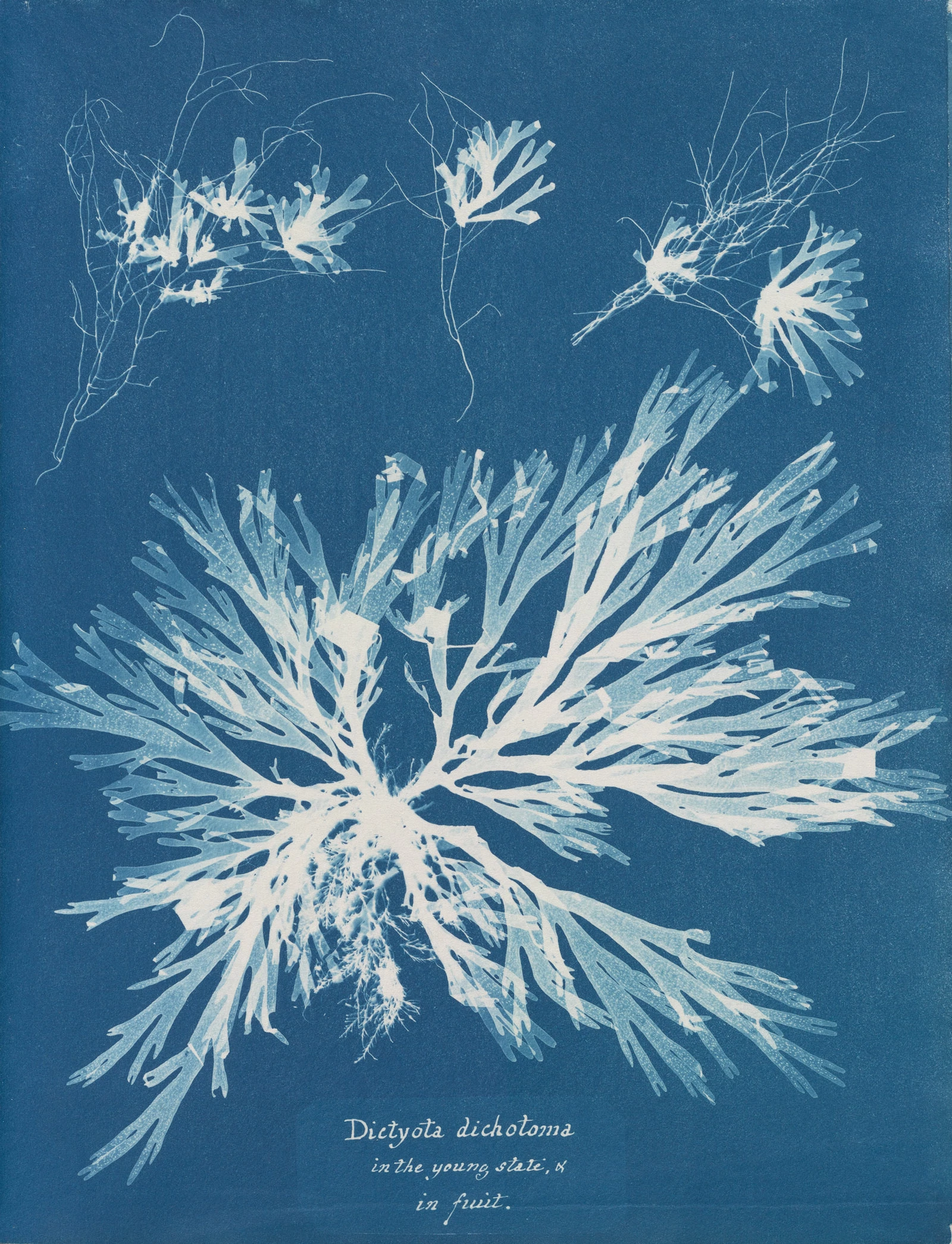

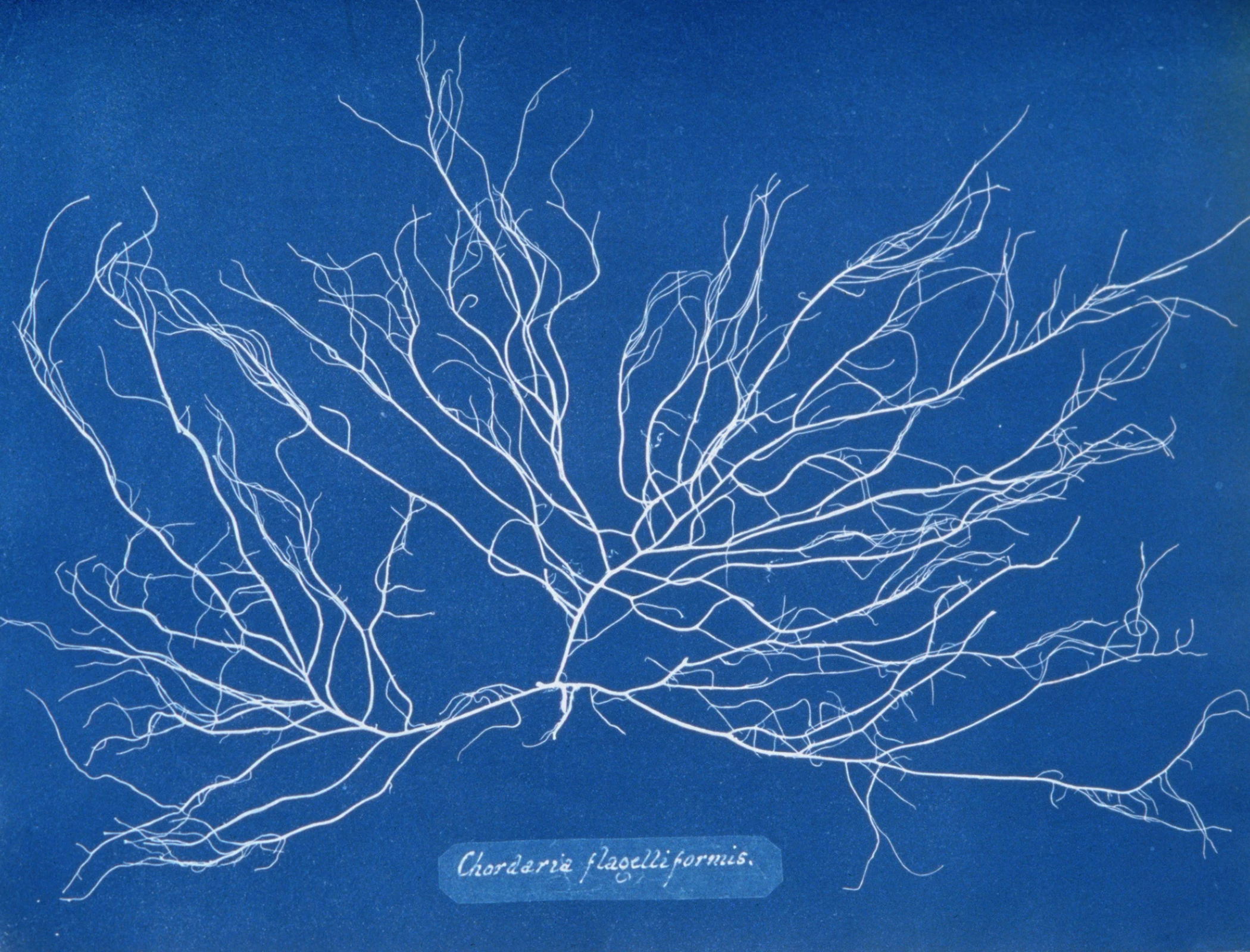

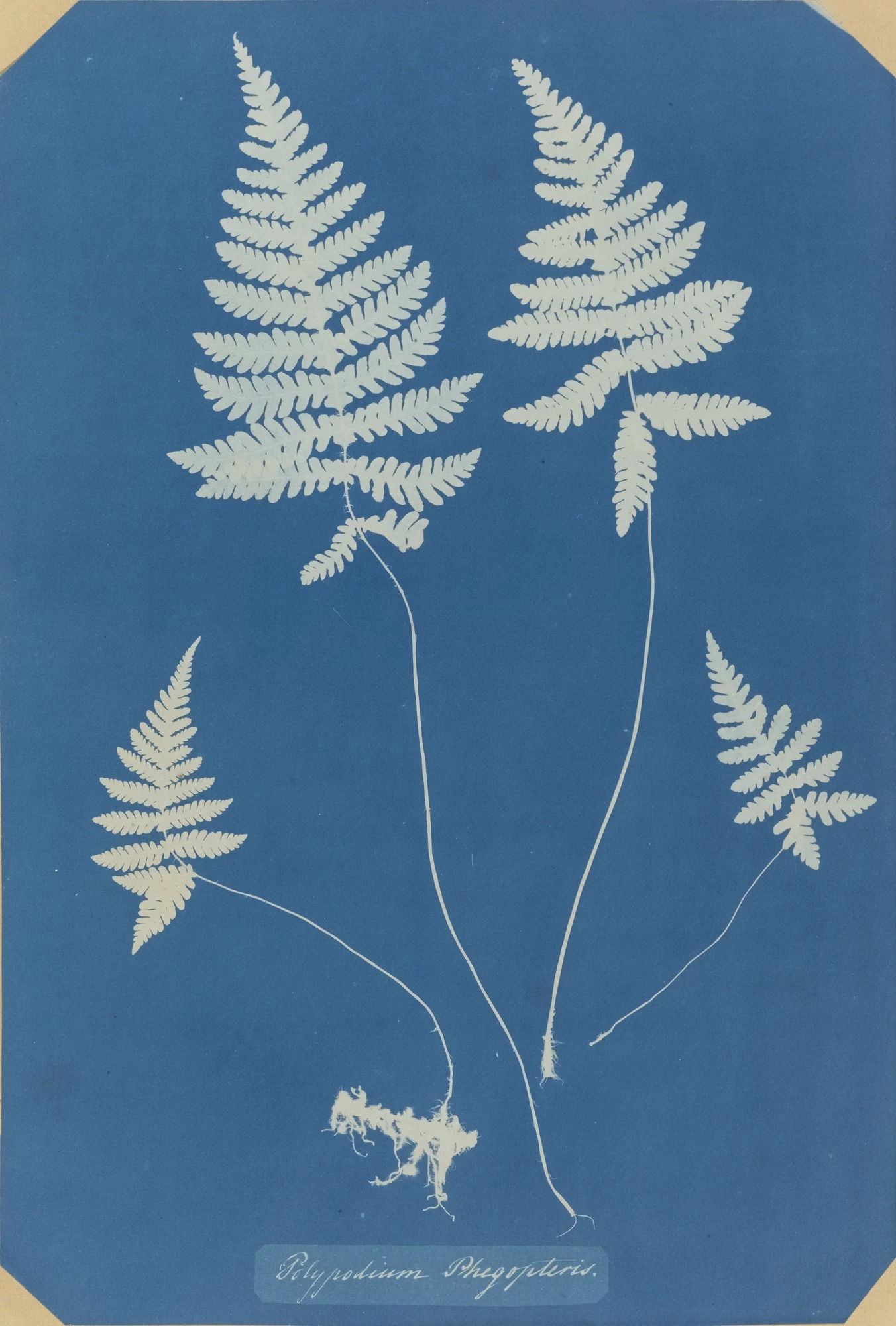

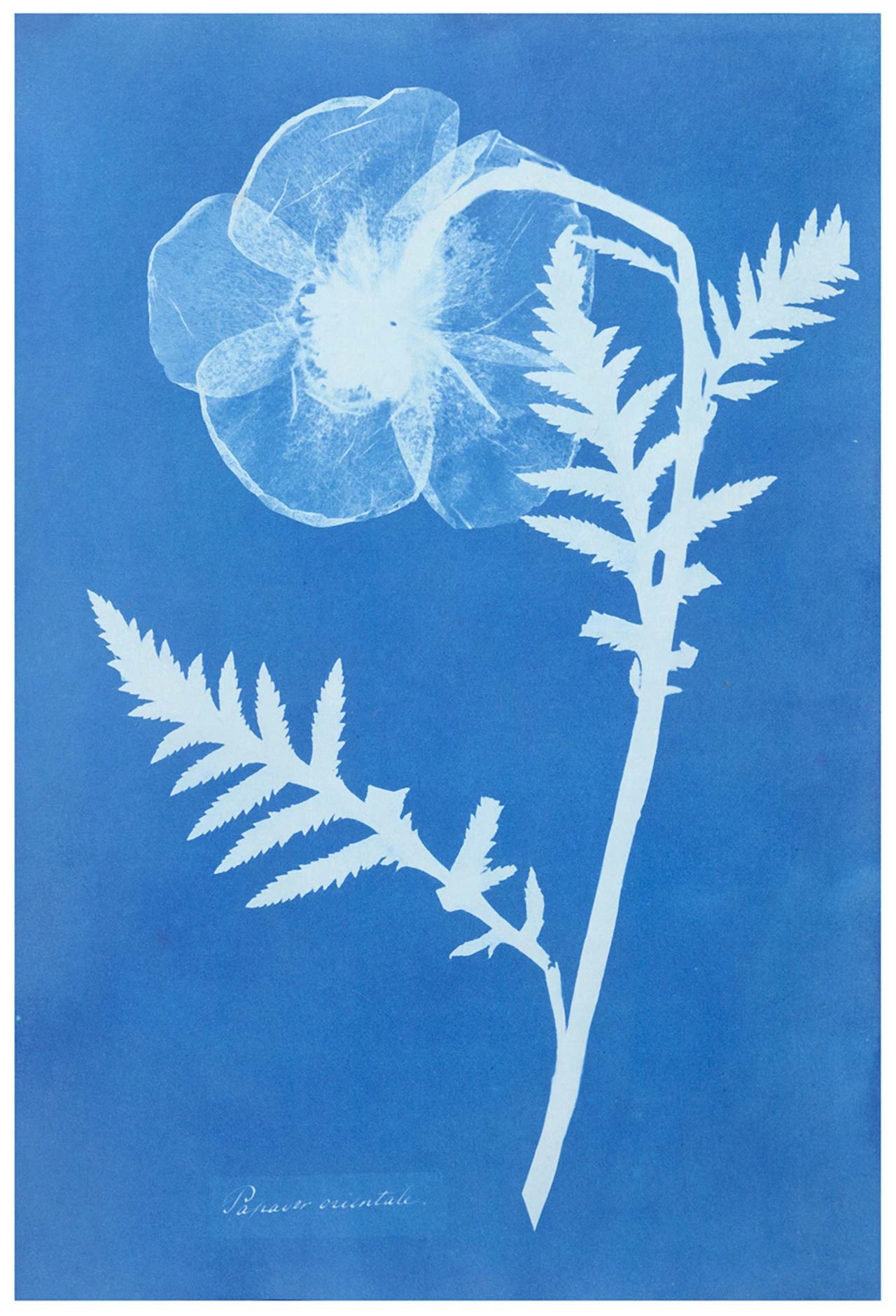

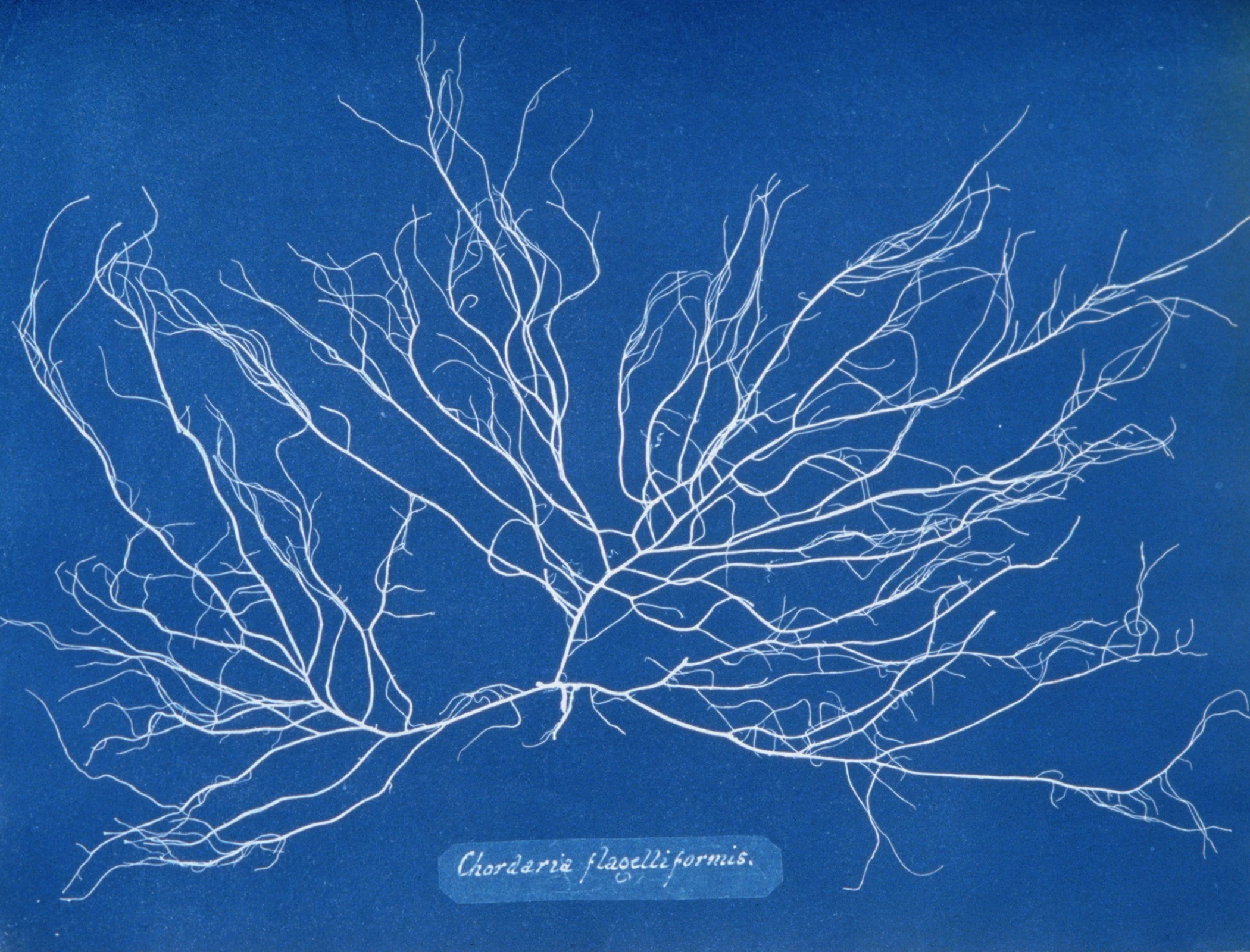

Electric blue: the first photographic book

An invention is only as interesting as its applications. In other words, nice invention, what can you do with it? The 1840s and 50s witnessed an international race to invent a reliable process for capturing photographic images, with all the drama you'd expect from a patent war over revolutionary tech. Henry Talbot, Daguerre, all vying for accolade and ownership. But the young botanist Anna Atkins got right to the heart of the matter—what can be done with a photographic process?

Anna Atkins was the daughter of John George Children, a chemist, mineralogist and zoologist employed working as a librarian at the British Museum. Anna’s mother died shortly after Anna’s birth, leaving Anna in the care of her father. As a bright young child, Anna had unparalleled access to the scientific community, and received a rigorous education from John.

We don't know when Anna began collecting botanical specimens, but we do know that her collection was already expansive when she married in 1825, and that it continued to grow after that. Eventually her botanical archive became so thorough and well-known that in 1839 Anna was granted a membership in the Botanical Society of London, one of the few scientific societies that allowed women to join.

And this is where invention meets application. One of John’s close friends and neighbors was the inventor Henry Hershel, who in 1840 was feverishly developing a new process for the transfer of photographic information. Full biography coming soon.