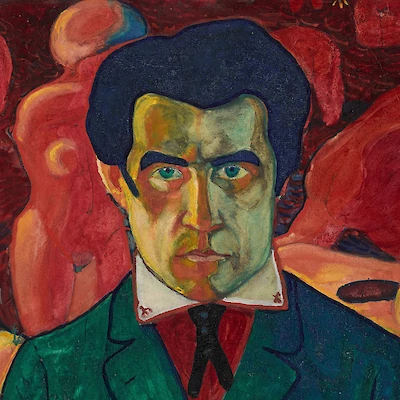

Kazimir Malevich

"Art does not need us, and it never did"

1879 – 1935Only when the conscious habit of seeing the little corners of nature, once the Madonnas and Venuses in pictures disappear, will we witness a purely painterly work of art. I have transformed myself in the zero of form and have fished myself out of the rubbishy slough of academic art.

I have destroyed the ring of the horizon and escaped the circle of objects, the horizon-ring that has imprisoned the artist and the forms of nature. This accursed ring, by continually revealing novelty after novelty, leads the artist away from the aim of destruction. And only cowardly consciousness and insolvency of creative power in an artist yield to this deception and establish their art on the forms of nature, afraid of losing the foundation on which the savage and the academy have based their art.

To reproduce beloved objects and little corners of nature is just like a thief being enraptured by his shackled legs. Only dull and impotent artists veil their work with sincerity. Art requires truth, not sincerity. Objects have vanished like smoke; to attain the new artistic culture, art advances toward creation as an end in itself and toward domination over the forms of nature.

The savage was the first to establish the principle of naturalism: in drawing a dot and five little sticks, he attempted to transmit his own image.

This first attempt laid the basis for the conscious imitation of nature’s forms. Hence arose the aim of approaching the face of nature as closely as possible. And all the artist’s efforts were directed toward the transmission of her creative forms. The first inscription of the savage’s primitive depiction gave birth to collective art, or the art of repetition. Collective, because the real man with his subtle range of feelings, psychology, and anatomy had not been discovered. The savage saw neither his outward image nor his inward state. His consciousness could see only the outline of a man, a beast, etc. And as his consciousness developed, so the outline of his depiction of nature grew more involved. The more his consciousness embraced nature, the more involved his work became, and the more his experience and skill increased. His consciousness developed in only one direction, toward nature’s creation and not toward new forms of art. Therefore his primitive depictions cannot be considered creative work. The distortion of reality in his depictions is the result of weak technique. Both technique and consciousness were only at the beginning of their development. And his pictures must not be considered art. Because unskillfulness is not art. He merely pointed the way to art.

Consequently, his original outline was a framework on which the generations hung new discovery after new discovery made in nature. And the outline became more and more involved and achieved its flowering in antiquity and the Renaissance. The masters of these two epochs depicted man in his complete form, both outward and inward. Man was assembled, and his inward state was expressed. But despite their enormous skill, they did not, however, perfect the savage’s idea: The reflection of nature on canvas, as in a mirror. And it is a mistake to suppose that their age was the most brilliant flower-ing of art and that the younger generation should at all costs aspire toward this ideal. This idea is false. It diverts young forces from the contemporary current of life and thereby deforms them. Their bodies fly in airplanes, but they cover art and life with the old robes of Neros and Titians. Hence they are unable to observe the new beauty of our modern life. Because they live by the beauty of past ages. That is why the realists, impressionists, cubism, futurism, and suprematism were not understood. The latter artists cast aside the robes of the past, came out into modern life, and found new beauty. And I say: That no torture chambers of the academies will withstand the days to come. Forms move and are born, and we are forever making new discoveries. And what we discover must not be concealed. And it is absurd to force our age into the old forms of a bygone age. The hollow of the past cannot contain the gigantic constructions and movement of our life. As in our life of technology: We cannot use the ships in which the Saracens sailed, and so in art we should seek forms that correspond to modern life. The technological side of our age advances further and further ahead, but people try to push art further and further back.

This is why all those people who follow their age are superior, greater, and worthier. And the realism of the nineteenth century is much greater than the ideal forms found in the aesthetic experience of the ages of the Renaissance and Greece. The masters of Rome and Greece, after they had attained a knowledge of human anatomy and produced a depiction that was to a certain extent realistic: were overrun by aesthetic taste, and their realism was pomaded and powdered with the taste of aestheticism. Hence their perfect line and nice colors. Aesthetic taste diverted them from the realism of the earth, and they reached the impasse of idealism. Their painting is a means of decorating a picture. Their knowledge was taken away from nature into closed studios, where pictures were manufactured for many centuries. That is why their art stopped short. They closed the doors behind them, thereby destroying their contact with nature. And that moment when they were gripped by the idealization of form should be considered the collapse of real art. Because art should not advance toward abbreviation or simplification, but toward complexity. The Venus de Milo is a graphic example of decline. It is not a real woman, but a parody. Angelo’s David is a deformation: His head and torso are modeled, as it were, from two incongruent forms. A fantastic head and a real torso. All the masters of the Renaissance achieved great results in anatomy. But they did not achieve veracity in their impression of the body. Their painting does not transmit the body, and their landscapes do not transmit living light, despite the fact that bluish veins can be seen in the bodies of their people. The art of naturalism is the savage’s idea, the aspiration to transmit what is seen, but not to create a new form. His creative will was in an embryonic state, but his impressions were more developed, which was the reason for his reproduction of reality.

Similarly it should not be assumed that his gift of creative will was developed in the classical painters. Because we see in their pictures only repetitions of the real forms of life in settings richer than those of their ancestor, the savage.

Similarly their composition should not be considered creation, for in most cases the arrangement of figures depends on the subject: a king’s procession, a court, etc. The king and the judge already determine the places on the canvas for the persons of secondary importance. Furthermore, the composition rests on the purely aesthetic basis of nice-ness of arrangement. Hence arranging furniture in a room is still not a creative process.

In repeating or tracing the forms of nature, we have nurtured our consciousness with a false conception of art. The work of the primitives was taken for creation. The classics also. If you put the same glass down twenty times, that’s also creation. Art, as the ability to transmit what we see onto a canvas, was considered creation. Is placing a samovar on a table also really creation? I think quite differently. The transmission of real objects onto a canvas is the art of skillful reproduction, that’s all. And between the art of creating and the art of repeating there is a great difference. To create means to live forever creating newer and newer things. And however much we arrange furniture about rooms, we will not extend or create a new form for them. And however many moonlit landscapes the artist paints, however many grazing cows and pretty sunsets, they will remain the same dear little cows and sunsets. Only in a much worse form. And in fact, whether an artist is a genius or not is determined by the number of cows he paints.

The artist can be a creator only when the forms on his picture have nothing in common with nature.

For art is the ability to create a construction that derives not from the interrelation of form and color and not on the basis of aesthetic taste in a construction’s compositional beauty, but on the basis of weight, speed, and direction of movement. Forms must be given life and the right to individual existence. Nature is a living picture, and we can admire her. We are the living heart of nature. We are the most valuable construction in this gigantic living picture. We are her living brain, which magnifies her life.

To reiterate nature is theft, and he who reiterates her is a thief — a non-entity who cannot give, but who likes to take things and claim them as their own (Counterfeiters). An artist is under a vow to be a free creator, but not a free robber. An artist is given talent in order that he may present to life his share of creation and swell the current of life, so versatile. Only in absolute creation will he acquire his right.

And this is possible when we free all art of philistine ideas and subject matter and teach our consciousness to see everything in nature not as real objects and forms, but as material, as masses from which forms must be made that have nothing in common with nature. Then the habit of seeing Madonnas and Venuses in pictures, with fat, flirtatious cupids, will disappear.

Color and texture are of the greatest value in painterly creation — they are the essence of painting; but this essence has always been killed by the subject. And if the masters of the Renaissance had discovered painterly surface, it would have been much nobler and more valuable than any Madonna or Gioconda. And any hewn pentagon or hexagon would have been a greater work of sculpture than the Venus de Milo or David. The principle of the savage is to aim to create art that repeats the real forms of nature. In intending to transmit the living form, they transmitted its corpse in the picture. The living was turned into a motionless, dead state. Everything was taken alive and pinned quivering to the canvas, just as insects are pinned in a collection.

But that was the time of Babel in terms of art.

They should have created, but they repeated; they should have deprived forms of content and meaning, but they enriched them with this burden. They should have dumped this burden, but they tied it around the neck of creative will. The art of painting, the word, sculpture, was a kind of camel, loaded with all the trash of odalisques, Salomes, princes, and princesses. Painting was the tie on the gentleman’s starched shirt and the pink corset drawing in the stomach. Painting was the aesthetic side of the object. But it was never an end in itself.

Artists were officials making an inventory of nature’s property, amateur collectors of zoology, botany, and archaeology. Nearer our time, young artists devoted themselves to pornography and turned painting into lascivious trash. There were no attempts at purely painterly tasks as such, without any appurtenances of real life.

There was no realism of painterly-form as an end in itself, and there was no creation.

The realist academists are the savages last descendants. They are the ones who go about in the worn out robes of the past. And again, as before, some have cast aside these greasy robes. And given the academy rag-and-bone man a slap in the face with their proclamation of futurism. They began in a mighty movement to hammer at the consciousness as if at nails in a stone wall. To pull you out of the catacombs into the speed of contemporaneity.

I assure that whoever has not trodden the path of futurism at as the exponent of modern life is condemned to crawl forever among the ancient tombs and feed on the leftovers of bygone ages.

Futurism opened up the “new” in modern life: the beauty of speed.

And through speed we move more swiftly. And we, who only yesterday were futurists, have reached new forms through speed, new relationships with nature and objects.

We have reached suprematism, abandoning futurism as a loophole through which those lagging behind will pass.

We have abandoned futurism, and we, bravest of the brave, have spat on the altar of its art. But can cowards spit on their idols— As we did yesterday!!!

I tell you, you will not see the new beauty and the truth until you venture to spit. Before us, all arts were old blouses, which are changed just like your silk petticoats. After throwing them away, you acquire new ones. Why do you not put on your grandmothers’ dresses, when you thrill to the pictures of their powdered portraits? This all confirms that your body is living in the modern age while your soul is clothed in your grandmother’s old bodice. This is why you find the Somovs, Kustodievs, and various such rag merchants so pleasant.

And I hate these secondhand-clothes dealers. Yesterday we, our heads proudly raised, defended futurism— Now with pride we spit on it. And I say that what we spat upon will be accepted. You, too, spit on the old dresses and clothe art in something new.

We rejected futurism not because it was outdated, and its end had come. No. The beauty of speed that it discovered is eternal, and the new will still be revealed to many. Since we run to our goal through the speed of futurism, our thought moves more swiftly, and whoever lives in futurism is nearer to this aim and further from the past.

And your lack of understanding is quite natural. Can a man who always goes about in a cabriolet really understand the experiences and impressions of one who travels in an express or flies through the air? The academy is a moldy vault in which art is being flagellated Gigantic wars, great inventions, conquest of the air, speed of travel, telephones, telegraphs, dreadnoughts are the realm of electricity.

But our young artists paint Neros and half-naked Roman warriors.

Honor to the futurists who forbade the painting of female hams, the painting of portraits and guitars in the moonlight. They made a huge step forward: they abandoned meat and glorified the machine.

But meat and the machine are the muscles of life. Both are the bodies that give life movement. It is here that two worlds have come together. The world of meat and the world of iron.

Both forms are the mediums of utilitarian reason. But the artist’s relationship to the forms of life’s objects requires elucidation.

Until now the artist always followed the object. Thus the new futurism follows the machine of today’s dynamism. These two kinds of art are the old and the new—futurism: they are behind the running forms. And the question arises: will this aim in the art of painting respond to its existence? No! Because in following the form of airplanes or motorcars, we shall always be anticipating the new cast-off forms of technological life. . . . And second: In following the form of things, we cannot arrive at painting as an end in itself, at spontaneous creation. Painting will remain the means of transmitting this or that condition of life’s forms. But the futurists forbade the painting of nudity not in the name of the liberation of painting and the word, so that they would become ends in themselves! But because of the changes in the technological side of life.

The new life of iron and the machine, the roar of motorcars, the brilliance of electric lights, the growling of propellors have awakened the soul, which was suffering in the catacombs of old reason and has emerged at the intersection of the paths of heaven and earth. If all artists were to see the crossroads of these heavenly paths, if they were to comprehend these monstrous runways and intersections of our bodies with the clouds in the heavens, then they would not paint chrysanthemums.

The dynamics of movement has suggested advocating the dynamics of painterly plasticity. But the efforts of the futurists to produce purely painterly plasticity as such were not met with success. They could not settle accounts with objectism, which would have made their task easier. When they had driven reason halfway from the field of the picture, from the old calloused habit of seeing everything naturally, they managed to make a picture of the new life of new things, but that is all.

In the transmission of movement, the cohesiveness of things disappeared as their flashing parts hid themselves among other running bodies. And in constructing the parts of the running objects, they tried to transmit only the impression of movement. But in order to transmit the movement of modern life, one must operate with its forms.

Which made it more complicated for the art of painting to reach its goal. But however it was done, consciously or unconsciously, for the sake of movement or for the sake of transmitting an impression, the cohesion of things was violated. And in this breakup and violation of cohesion lay the latent meaning that had been concealed by the naturalistic purpose. Underlying this destruction lay primarily not the transmission of the movement of objects, but their destruction for the sake of pure painterly essence, i.e., toward attainment of nonobjective creation. The rapid interchange of objects struck the new naturalists — the futurists—and they began to seek means of transmitting it. Hence the construction of the futurist pictures that you have seen arose from the discovery of points on a plane where the placing of real objects during their explosion or confrontation would impart a sense of time at a maximum speed. These points can be discovered independently of the physical law of natural perspective. Thus we see in futurist pictures the appearance of clouds, horses, wheels, and various other objects in places not corresponding to nature.

The state of the object has become more important than its essence and meaning. We see an extraordinary picture. A new order of objects makes reason shudder. The mob howled and spat, critics rushed at the artist like dogs at the gate. (Shame on them.)

The futurists displayed enormous strength of will in destroying the habit of the old mind, in flaying the hardened skin of academism and spitting in the face of the old common sense.

After rejecting reason, the futurists proclaimed intuition as the subconscious. But they created their pictures not out of the subconscious forms of intuition, but used the forms of utilitarian reason. Consequently, only the discovery of the difference between the two lives of the old and the new art will fall to the lot of intuitive feeling.

We do not see the subconscious in the actual construction of the picture. Rather do we see the conscious calculation of construction.

In a futurist picture there is a mass of objects. They are scattered about the surface in an order unnatural to life. The conglomeration of objects is acquired not through intuitive sense, but through a purely visual impression, while the building, the construction, of the picture is done with the intention of achieving an impression. And the sense of the subconscious falls away. Consequently, we have nothing purely intuitive in the picture. Beauty, too, if it is encountered, proceeds from aesthetic taste. The intuitive, I think, should manifest itself when forms are unconscious and have no response.

I consider that the intuitive in art had to be understood as the aim of our sense of search for objects. And it followed a purely conscious path, blazing its decisive trail through the artist. (Its form is like two types of consciousness fighting between themselves.) But the consciousness, accustomed to the training of utilitarian reason, could not agree with the sense that led to the destruction of objectism. The artist did not understand this aim and, submitting to this sense, betrayed reason and distorted form. The art of utilitarian reason has a definite purpose.

But intuitive creation does not have a utilitarian purpose. Hitherto we have had no such manifestation of intuition in art. All pictures in art follow the creative forms of a utilitarian order. All the naturalists’ pictures have the same form as in nature.

Intuitive form should arise out of nothing. Just as reason, creating things for everyday life, extracts them from nothing and perfects them. Thus the forms of utilitarian reason are superior to any depictions in pictures. They are superior because they are alive and have proceeded from material that has been given a new form for the new life. Here is the Divine ordering crystals to assume another form of existence. There should be a miracle in the creation of art, as well.

But the realists in transferring living things onto the canvas, deprive their life of movement. And our academies teach dead, not living, painting. Hitherto intuitive feeling has been directed to drag newer and newer forms into our world from some kind of bottomless void.

But there has been no proof of this in art, and there should be. And I feel that it does already exist in a real form and quite consciously.

The artist should know what, and why, things happen in his pictures. Previously he lived in some sort of mood. He waited for the moonrise and twilight, put green shades on his lamps, and all this tuned him up like a violin. But if you asked him why the face on his canvas was crooked, or green, he could not give an exact answer.

“I want it like that, I like it like that. ...” Ultimately, this desire was ascribed to creative will. Consequently, the intuitive feeling did not speak clearly. And thereafter its state became not only subconscious but completely unconscious. These concepts were all mixed together in pictures. The picture was half-real, half-distorted.

Being a painter, I ought to say why people’s faces are painted green and red in pictures. Painting is paint and color; it lies within our organism. Its outbursts are great and demanding. My nervous system is colored by them. My brain burns with their color. But color was oppressed by common sense, was enslaved by it. And the spirit of color weakened and died out. But when it conquered common sense, then its colors flowed onto the repellent form of real things. The colors matured, but their form did not mature in the consciousness. This is why faces and bodies were red, green, and blue. But this was the herald leading to the creation of painterly forms as ends in themselves.

Now it is essential to shape the body and lend it a living form in real life. And this will happen when forms emerge from painterly masses, that is they will arise just as utilitarian forms arose. Such forms will not be repetitions of living things in life, but will themselves be a living thing.

A painted surface is a real, living form.

Intuitive feeling is now passing to consciousness; no longer is it subconscious. Even, rather, vice versa — it always was conscious, but the artist just could not understand its demands.

The forms of suprematism, the new painterly realism, already testify to the construction of forms out of nothing, discovered by intuitive reason. The cubist attempt to distort real form and its breakup of objects were aimed at giving the creative will the independent life of its created forms.

If we take any point in a futurist picture, we shall find either something that is coming or going, or a confined space. But we shall not find an independent, individual painterly surface. Here the painting is nothing but the outer garment of things. And each form of the object was painterly insofar as its form was necessary to its existence, and not vice versa. The futurists advocate the dynamics of painterly plasticity as the most important aspect of a painting. But in failing to destroy objectivism, they achieve only the dynamics of things. Therefore futurist paintings and all those of past artists can be reduced from twenty colors to one, without sacrificing their impression. Repin’s picture of Ivan the Terrible could be deprived of color, and it will still give us the same impressions of horror as it does in color. The subject will always kill color, and we will not notice it. Whereas faces painted green and red kill the subject to a certain extent, and the color is more noticeable. And color is what a painter lives by, so it is the most important thing. And here I have arrived at pure color forms. And suprematism is the purely painterly art of color whose independence cannot be reduced to a single color. The galloping of a horse can be transmitted with a single tone of pencil. But it is impossible to transmit the movement of red, green, or blue masses with a single pencil.

Painters should abandon subject matter and objects if they wish to be pure painters.

The demand to achieve the dynamics of painterly plasticity points to the impulse of painterly masses to emerge from the object and arrive at color as an end in itself, at the domination of purely painterly forms as ends in themselves over content and things, at nonobjective suprematism—at the new painterly realism, at absolute creation.

Futurism approaches the dynamism of painting through the academism of And both endeavors essentially aspire to suprematism in painting. If we examine the art cubism, the question arises what energy in objects incited the intuitive feeling to activity; we shall see that painterly energy was of secondary importance. The object itself, as well as its essence, purpose, sense, or the fullness of its representation (as the cubists thought), was also unnecessary. Hitherto it has seemed that the beauty of objects is preserved when they are transmitted whole onto the picture, and moreover, that their essence is evident in the coarseness or simplification of line. But it transpired that one more situation was found in objects—which reveals a new beauty to us. Namely: intuitive feeling discovered in objects the energy of dissonance, a dissonance obtained from the confrontation of two contrasting ideas. Objects contain a mass of temporal moments. Their forms are diverse, and consequently, the ways in which they are painted are diverse. All these temporal aspects of things and their anatomy (the rings of a tree) have become more important than their essence and meaning. And these new situations were adopted by the cubists as a means of constructing pictures. Moreover, these means were constructed so that the unexpected confrontation of two forms would produce a dissonance of maximum force and tension. And the scale of each form is arbitrary. Which justifies the appearance of parts of real objects in places that do not correspond to nature.

In achieving this new beauty, or simply energy, we have freed ourselves from the impression of the object’s wholeness. The millstone around the neck of painting is beginning to crack.

An object painted according to the principle of cubism can be considered finished when its dissonances are exhausted. Nevertheless, repetitive forms should be omitted by the artist since they are mere reiterations. But if the artist finds little tension in the picture, he is free to take them from another object. Consequently, in cubism the principle of transmitting objects does not arise. A picture is made, but the object is not transmitted. Hence this conclusion: Over the past millennia, the artist has striven to approach the depiction of an object as closely as possible, to transmit its essence and meaning; then in our era of Cubism the artist destroyed objects together with their meaning, essence and purpose.

A new picture has arisen from their fragments. Objects have vanished like smoke, for the sake of the new culture of art. Cubism, futurism, and the Wanderers differ in their aims, but are almost equal in a painterly sense. Cubism builds its pictures from the forms of lines and from a variety of painterly textures, and in this case, words and letters are introduced as a confrontation of various forms in the picture. Its graphic meaning is important. It is all for the sake of achieving dissonance. And this proves that the aim of painting is the one least touched upon. Because the construction of such forms is based more on actual superimposition than on coloring, which can be obtained simply by black and white paint or by drawing. To sum up: Any painted surface turned into a convex painterly relief is an artificial, colored sculpture, and any relief turned into surface is painting. The proof of intuitive creation in the art of painting was false, for distortion is the result of the inner struggle of intuition in the form of the real.

Intuition is a new reason, consciously creating forms. But the artist, enslaved by utilitarian reason, wages an unconscious struggle, now submitting to an object, now distorting it. Gauguin, fleeing from culture to the savages, and discovering more freedom in the primitives than in academism, found himself subject to intuitive reason. He sought something simple, distorted, coarse. This was the searching of his creative will. At all costs not to paint as the eye of his common sense saw. He found colors but did not find form, and he did not find it because common sense showed him the absurdity of painting anything except nature. And so he hung his great creative force on the bony skeleton of man, where it shriveled up. Many warriors and bearers of great talent have hung it up like washing on a fence.

And all this was done out of love for nature’s little nooks. And let the authorities not hinder us from warning our generation against the clothes stands that they have become so fond of and that keep them so warm.

The efforts of the art authorities to direct art along the path of common sense annulled creation. And with the most talented people, real form is distortion. Distortion was driven by the most talented to the point of disappearance, but it did not go outside the bounds of zero. But I have transformed myself in the zero of form and through zero have reached creation, that is, suprematism, the new painterly realism — nonobjective creation.

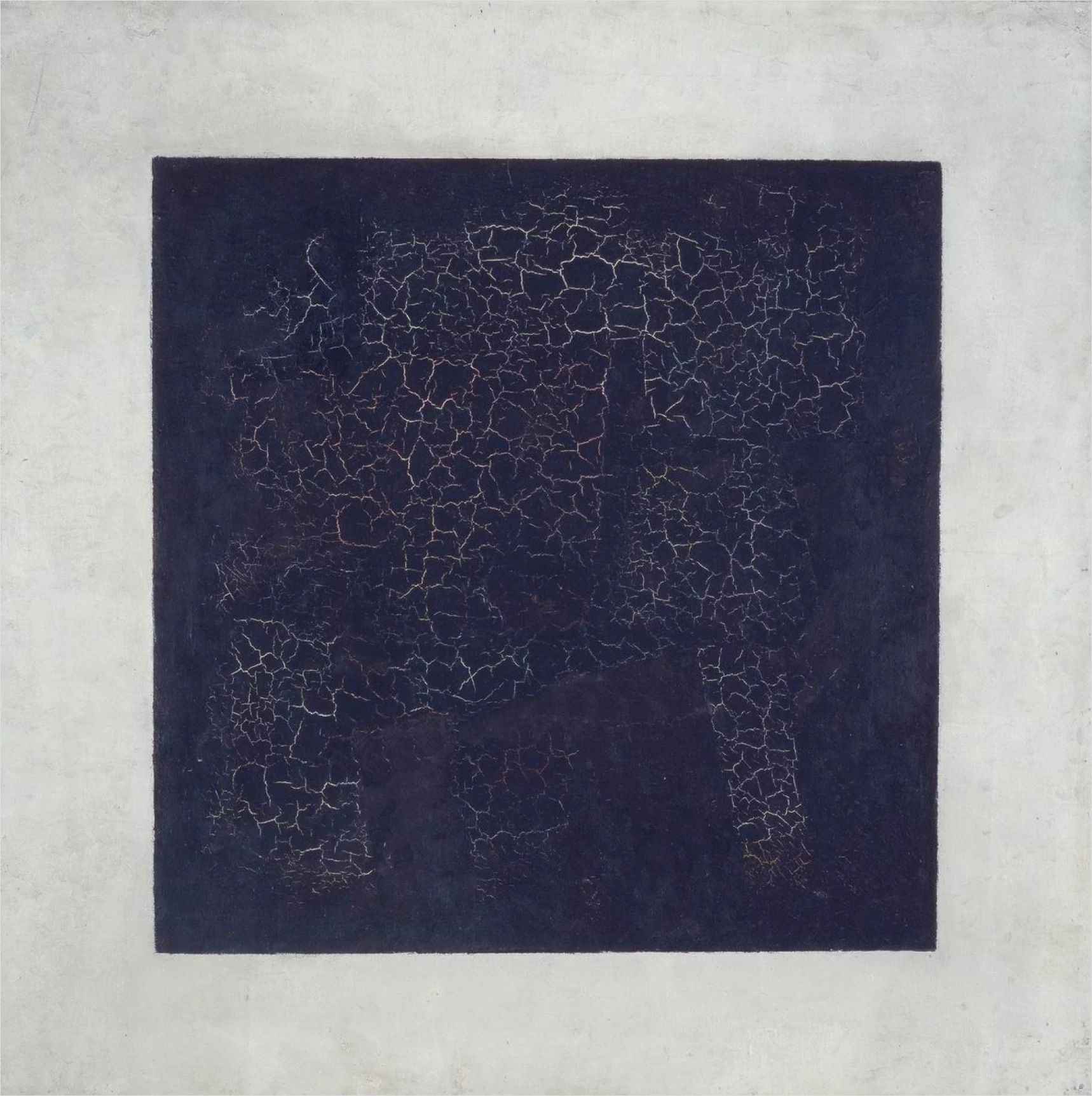

Suprematism is the beginning of a new culture: the savage is conquered like the ape. There is no longer love of little nooks, there is no longer love for which the truth of art was betrayed. The square is not a subconscious form. It is the creation of intuitive reason.

The face of the new art.

The square is a living, regal infant. The first step of pure creation in art. Before it there were naive distortions and copies of nature. Our world of art has become new, nonobjective, pure. Everything has disappeared; a mass of material is left from which a new form will be built. In the art of suprematism, forms will live, like all living forms of nature. These forms announce that man has attained his equilibrium; he has left the level of single reason and reached one of double reason. (Utilitarian reason and intuitive reason.)

The new painterly realism is a painterly one precisely because it has no realism of mountains, sky, water… Hitherto there has been a realism of objects, but not of painterly, colored units, which are constructed so that they depend neither on form, nor on color, nor on their position vis-a-vis each other.

Each form is free and individual. Each form is a world. Any painterly surface is more alive than any face from which a pair of eyes and a smile protrude. A face painted in a picture gives a pitiful parody of life, and this allusion is merely a reminder of the living. But a surface lives; it has been born. A coffin reminds us of the dead; a picture, of the living.

This is why it is strange to look at a red or black painted surface. This is why people snigger and spit at the exhibitions of new trends. Art and its new aim have always been a spittoon. But cats get used to one place, and it is difficult to house-train them to a new one. For such people, art is quite unnecessary, as long as their grandmothers and favorite little nooks of lilac groves are painted. Everything runs from the past to the future, but everything should live in the present, for in the future the apple trees will shed their blossoms.

Tomorrow will wipe away the vestige of the present, and you are too late for the current of life. The mire of the past, like a millstone, will drag you into the slough. This is why I hate those who supply уоц with monuments to the dead. The academy and the critics are this millstone round your neck. The old realism is the movement that seeks to transmit living nature. They carry on just as in the times of the Grand Inquisition. Their aim is ridiculous because they want at all costs to force what they take from nature to live on the canvas. At the same time as everything is breathing and running, their frozen poses are in pictures. And this torture is worse than breaking on the wheel. Sculptured statues, inspired, hence living, have stopped dead, posed as running. Isn't this torture? Enclosing the soul in marble and then mocking the living. But you are proud of an artist who knows how to torture. You put birds in a cage for pleasure as well. And for the sake of knowledge, you keep animals in zoological gardens. I am happy to have broken out of that inquisition torture chamber, academism.

I have arrived at the surface and can arrive at the dimension of the living body. But I shall use the dimension from which I shall create the new. I have released all the birds from the eternal cage and flung open the gates to the animals in the zoological gardens. May they tear to bits and devour the leftovers of your art. And may the freed bear bathe his body amid the flows of the frozen north and not languish in the aquarium of distilled water in the academic garden.

You go into raptures over a picture’s composition, but in fact, composition is the death sentence for a figure condemned by the artist to an eternal pose. Your rapture is the confirmation of this sentence.

The group of suprematists — K. Malevich, I. Puni, M. Menkov, I. Klyun, K. Boguslavskaya, and Rozanova — has waged the struggle for the liberation of objects from the obligations of art. And appeals to the academy to renounce the inquisition of nature.

Idealism and the demands of aesthetic sense are are the instruments of torture. The idealization of the human form is the mortification of the many lines of living muscle. Aestheticism is the garbage of intuitive feeling. You all wish to see pieces of living nature on the hooks of your walls. Just as Nero admired the torn bodies of people and animals from the zoological garden.

I say to all: Abandon love, abandon aestheticism, abandon the baggage of wisdom, for in the new culture, your wisdom is ridiculous and insignificant. I have untied the knots of wisdom and liberated the consciousness of color! Hurry up and shed the hardened skin of centuries, so that you can catch up with us more easily.

I have overcome the impossible and made gulfs with my breath.

You are caught in the nets of the horizon, like fish!

We, suprematists, throw open the way to you.

Hurry!

For tomorrow you will not recognize us.