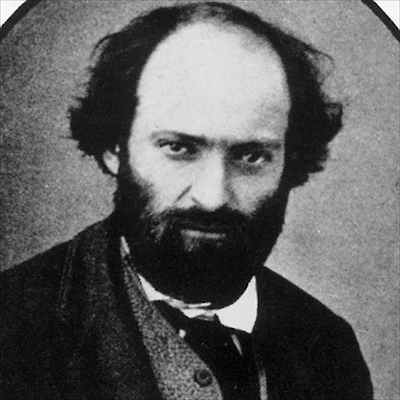

Paul Cézanne

A lifelong struggle to capture the intensity of life

1839 – 1906Aix-en-Provence, 15 April 1904

Dear Monsieur Bernard,

By the time this letter reaches you, you will very probably have received one coming from Belgium, I think, and addressed to you via the Rue Boulegon. I am happy to have the evidence of warm sympathy in art which you so kindly give me in the form of your letter.

Allow me to repeat what I said when you were here: deal with nature by means of the Cylinder, the sphere and the cone, all placed in perspective, so that each side of an object or a plane is directed towards a central point. Lines parallel to the horizon give breadth, a section of nature or, if you prefer, of the spectacle spread before our eyes by the Pater Omnipotens Aeterne Deus. Lines perpendicular to that horizon give depth. But for us men, nature has more depth than surface, hence the need to introduce in our vibrations of light, represented by reds and yellows, enough blue tints to give a feeling of air.

I would like to say that I have had another look at your study of the ground floor of the studio, it is good. All you need do, I think, is to continue along these lines, you have an understanding of what ought to be done, and you will soon be able to turn your back on the Gauguins and Van Goghs! Please thank Mme Bernard for her kind remembrance of the undersigned, give the children a kiss from ‘Père Goriot', and my best respects to your family.

Aix-en-Provence, 23 December 1904

My dear Bernard,

I have received your good letter from Naples. I will not launch out into aesthetic reflections with you. Yes, I approve of your admiration for the doughtiest Venetian of them all; we extol Tintoretto. Your need to find moral and intellectual support in works which will certainly never be excelled, keeps you perpetually on the alert, on an unceasing quest for the half-perceived methods that will surely bring you to a sense of your means of expression in contact with nature; and once you master those, you can be certain that you will rediscover, without effort and in contact with nature, the means employed by the four or five great Venetian painters.

This is what happens, unquestionably -- I am positive: an optical sensation is produced in our visual organ, which leads us to classify as light, half-tone or quarter-tone, the planes represented by sensations of color. (Thus, light does not exist for the painter.) As long as, inevitably, one proceeds from black to white, the former of these abstractions being a kind of point of rest both for eye and brain, we flounder about, we cannot achieve self-mastery, get possession of ourselves. During this period (I tend to repeat myself, inevitably) we turn to the admirable works handed down to us through the ages, in which we find comfort and support, like a plank to the swimmer. --Everything you say in your letter is quite true.

I am glad to hear that Madame Bernard, yourself and the children are all well. My wife and son are in Paris at the moment. We shall be together again soon, I trust. I hope to answer the principal points in your good letter so far as possible. Please ask Madame Bernard to accept my respectful greetings and give Antoine and Irène a kiss from me. As for you, my dear confrère, I wish you a happy New Year, with a warm clasp of the hand.

P. Cézanne

Aix-en-Provence, 23 October 1905

My dear Bernard,

I value your letters for two reasons, the first of which is entirely selfish since their arrival jerks me out of the monotony induced by the uninterrupted pursuit of my one and only aim, which, at moments of physical fatigue, brings on a sort of intellectual exhaustion, and the second is the opportunity they give me of harking back, rather too constantly no doubt, to an account of the obstinacy with which I pursue he attempt to render that part of nature which, when it comes before our eyes, presents us with a picture. The point to be made clear is that, whatever may be our temperament, or our power in the presence of nature, we have to render what we actually see, forgetting everything that appeared before our own time. Which, I think, should enable the artist to express his personality to the full, be it large or small.

Now that I am an old man, about seventy, the sensations of color which produce light give rise to abstractions that prevent me from covering my canvas, and from trying to define the outlines of objects when their points of contact are tenuous and delicate; with the result that my image or picture is incomplete. For another thing, the planes become confused, superimposed; hence Neo-Impressionism, where everything is outlined in black, an error which must be uncompromisingly rejected. And nature, if consulted, shows us how to achieve this aim.

Indeed I remembered you were at Tonnerre, but owing to the difficulties I meet with in trying to settle down at home I have put myself entirely in the hands of my family, with the result that they arrange what suits themselves and tend to forget me. Such is life; at my age I should have more experience and make use of it for the good of all. I owe you the truth in painting, and I will give it to you.

Please give my respects to Madame Bernard; the children I am bound to be fond of, St Vincent de Paul being the one to whom I should most commend myself. Your old

Paul Cézanne

A warm hand-clasp, and push ahead. The visual sense, as it develops in us by dint of study, teaches us to see.