What happens to art when you strip away all its depictions of history, grand vistas, languorous nudes, and human faces to tickle our fusiform gyrus, leaving only mundane objects represented in shallow, nondescript space? Can a bowl of fruit in a dark room be as compelling as Saint George slaying a Dragon? For the answer, we turn to Fede Galizia.

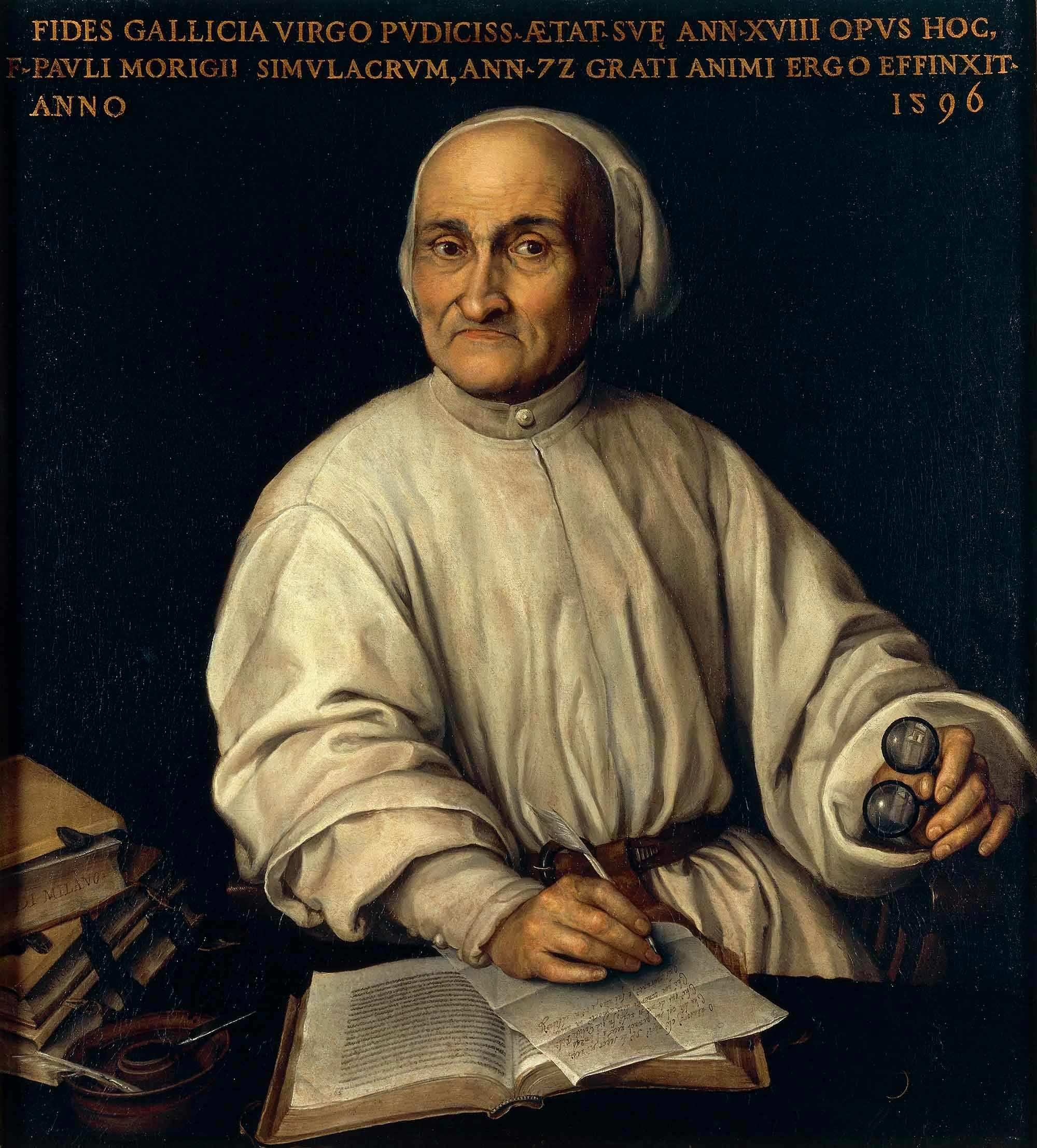

For a woman living in 16th century Europe, one of the very few ways to learn art was to be born into a family of artists. Lucky for young Fede, she was born in 1578 to Nunzio Galizia, a painter and miniaturist from Trento. Details about Fede’s early life are scarce, but whether her instruction was formal or through the osmosis of a childhood spent in the studio, by the time she was twelve the popular art critic Gian Paolo Lomazzo described her as “devoting herself to the imitation of our most excellent artists.” By seventeen Galizia was taking portrait commissions, including a portrait of Jesuit historian Paolo Morigia he later described as a work “of such excellence, and such a good likeness, that one could not desire anything more.” By twenty, Galizia was internationally known and a sought after painter.

Galizia’s portraits were in demand in part for their unfiltered naturalism. In her portrait of Paolo Morigia, the historian’s thin lips and underbite are depicted unflinchingly, but this attention to detail also captures a patient curiosity in his eyes, reflections in the lenses of his glasses, and every wrinkle and fold in the books piled on his desk. This eye for detail enabled Galizia to revolutionize the humble genre of still life.

Still life as we know it was relatively undeveloped at the time Galizia was working. Previous generations of European artists had depicted flowers, foods and other inanimate objects, but they were typically iconographic, representing moral virtues or sins. Others, like Albrecht Dürer’s painstaking depictions of plants and animals, were detailed studies of nature, foreshadowing the scientific illustrations of the Enlightenment. But Galizia’s approach to still life was startlingly contemporary—she painted objects like she painted people.

Take as a counterpoint the trickster god of Baroque art, Caravaggio, who painted this basket of fruit when Galizia was about 18. Caravaggio’s composition is dramatic, with saw toothed leaves arching over a bright background. Grapes and apples and the basket that holds them are impeccably rendered, but the piece is defined by its silhouette, the negative space around the still life. In contrast, Galizia zooms in, setting her still lifes against dark backgrounds, viewed from just above, as we might look at fruits displayed on a table. Rather than create a dramatic gestalt, her focus zooms in to each individual peach and flower, rendering them with detail but without fussy dramatization. Each object is a whole, singular entity in conversation with the others. It’s a surprisingly modern approach to the genre, almost a precursor to the Modernist stylings of Cezanne and Morandi. Galizia gave mundane objects life.

By the time she passed away at age 61, Galizia had painted at least forty-four still lifes, more than two-thirds of the works currently attributed to her. In an era where ‘great art’ was dominated by male artists fixated on large-scale religious and history painting, Galizia’s careful observation and attentive brush formed a foundation for the developing genre of still life. Historian Rachel Maggart perfectly described Galizia’s works, saying “they intermingled science and the decorative and craft arts in a secularist spirit, raising botanical and zoological subject matter to the level of religious devotion.” The high drama of history painting will always earn praise, but sometimes it’s nice to slow down, take a deep breath, and contemplate a peach.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Fede Galizia? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.