You probably discovered Joseph Ducreux from the meme, lord knows I did. A dapper gentleman in a powdered wig is pointing at you, and he's got some advice. Archaic Rap is an old meme by now, but it revived an artist whose humor and charm allowed him to navigate the cloak and dagger world of international politics on the eve of the French Revolution, reinvent the self-portrait genre, and eventually be reborn as a modern day meme-lord. What's the real story of Joseph Ducreux? Buckle up, this is a wild one.

First, let's set the stage. After the Seven Years' War, France had ceded their territories in North America to Great Britain. It was a devastating loss for the French morale and economy, but the French statesman and negotiator Étienne François, Duc de Choiseul, had a plan. He would rebuild a prosperous France by brokering an alliance with the Austrian Empire through an arranged marriage between the future Louis XVI of France and the Archduchess of Austria, Marie-Antoinette.

The royal matchmaking began in 1766 in secret, when Marie-Antoinette was 11 and the French dauphin was 12. There were exchanges of royal presents of fresh pears and peaches, sent fresh in January, and after a couple of years the young Louis expressed "curiosity to know the princess, at least in painting." So it's 1769, and the political future of the European continent hangs on a portrait.

At first, the Austrian Empress sent a pocket-sized miniature of her Marie, but Louis wanted to see the princess life-sized, and offered to send a French painter to Austria. The obvious choice was the fashionable portraitist François-Hubert Drouais, but Drouais would need to drop his existing commissions and asked for 80,000 livres to cover the loss, something around 2 million USD today. Too expensive, even for the King. As the royal eye desperately searched for a discrete, affordable artist with an eye for flattery, Choiseul stepped in and made the call: Ducreux will do it.

Joseph Ducreux was born on June 26, 1735, in Nancy, in northeast France, but soon moved to the Lorraine resort town of Lunéville where his father, Charles, worked as first painter to Stanisław Leszczyński, the retired king of Poland. We assume that young Joseph learned the trade of portraiture from his father and sometime before 1760 moved to the Saint-Germain des Prez district of Paris, married Philippine-Rose Cosse, and became friends with the artist Jean-Baptiste Greuze. Greuze was a bit of a mentor to Ducreux, and offered some of the best art advice of all time: "Undertake only what you can do in your essence and hasten slowly." And of portraits: "be sharp if you cannot be true."

During these early years in Paris Ducreux learned his signature technique, soft, subtle portraits in pastel, likely from the the Rococo portraitist Maurice Quentin de La Tour, though biographer Georgette Lyon proposed that that Ducreux learned from careful imitation, rather than active study. "La Tour did not have a workshop and we have found nothing to confirm that the eldest advised the younger directly. Both had very bad tempers, and their friendship would certainly not have lasted if they had seen each other every day." Either way, by 1762 Ducreux was a successful portrait artist taking commissions from wealthy Parisians.

In 1764 Ducreux's work made a big splash in an exhibition at the Hotel d'Aligre, earning him membership in the Academy of Saint-Luc. This Academy was a guild of painters and sculptors who were unable to break into the French Royal Academy. With Ducreux as one of their rising stars, they soon gained enough attention to provoke the jealousy of Pierre Mignard, first painter to the king of France. In 1776 Mignard manipulated financial reforms to snuff out the Academy, leaving Joseph Ducreux without academic backing and trying to support his baby son Adrien-Charles, when the diplomat Choiseul appeared with a request.

To Choiseul, Joseph Ducreux must have been the perfect choice. He had a history with the Austrian court from his time in Lorraine, he'd worked with the French royal event-planners the Menus-Plaisirs du Roi, earning an above-average (but not outlandish) wage, and apparently he had good manners. Bitter old Mignard was pissed, and in later years derided Ducreux's work in bitchy letters to friends, but the deal was done. In a letter to the diplomat Marquis de Durfort, Choiseul wrote:

"You have done me the honor of telling me that the Empress Queen of Hungary would not disapprove of a French painter being commissioned to paint the portraits of the Archduchesses. I gave an account of it to the King, and His Majesty, consequently, chose Ducreux, one of his regular painters, to fill this commission. He is to leave in a few days and on his arrival in Vienna will come to you, Sir, to ask you to direct his steps and introduce him to the Imperial family."

Ducreux left Paris in February 1769, accompanied by a hairdresser named Larseneur whose mission was to correct Marie-Antoinette's overly high hairline, ensuring that in her portrait "the forehead appears better furnished." A veritable flurry of letters sped back and forth between the two courts as the painter and the hairdresser set about their work. But one commission turned into many, and Ducreux was sidelined mid-portrait on the Empress's orders to paint the Archduchesses Christine, Thérèse, Elisabeth, and Prince Albert of Saxony. Sitting for a portrait was a long, boring process, but Ducreux must have kept it fun, another letter describing him as a charming entertainer "whose gaiety and renowned good grace of his remarks could facilitate the patience of the child."

As Ducreux's time in Austria continued, the French court began to get impatient. Word arrived from Durfort that the artist had to start Marie's portrait over after his secondary sessions. It took three months for the Portrait of Marie Antoinette to be completed and delivered, and finally, on May 18 the verdict arrived:

“The King expressed great satisfaction with the portraits of the Most Serene Archduchesses Marie-Antoinette and Marie-Thérèse. On rising the day before yesterday all the assistants, foreign ministers and courtiers saw the portrait in question. When asked about it, I suggested that if we are to believe public rumor, the reality must far surpass the portrait in beauty.”

But this was just the beginning—the French court requested portraits of Archduchess Christine dressed in blue and Archduchess Elisabeth in green, and each portrait had to be painted and then duplicated for the Austrian court by their copiest, an artist named Krautzinger who apparently modified the portraits to be a bit more Austrian. By June, an entire gallery's worth of Austrian nobility had been painted by Ducreux and shipped to Louis's court. Finally, ten months after his arrival in Austria, Ducreux finished his mission, and returned to Paris with his final commissions: portraits of the Empress-Queen, the Emperor, the Archdukes Ferdinand and Maxi Milien, and a second portrait of Marie.

On the 7th of February 1770, Louis XV formally requested the hand of Marie Antoinette in marriage to his son Louis XVI, and on 16 May 1770 the young couple was married in the Palace of Versailles. Ducreux's mission had succeeded, and his instrumental role in the union was explicitly recognized when Marie bestowed on him a new title: Painter of the King and of Her Imperial and Apostolic Majesty the Queen of Hungary and Bohemia.

After his whirlwind tour of Austrian royalty, Ducreux settled into his new life back in Paris as a painter of status. He had two more children and took on a steady stream of lucrative commissions. While productive, Ducreux was never allowed entry to the Royal Academy. After presenting his work three times and receiving three rejections, the art dealer Johann Georg Wille wrote that Ducreux "said and wrote so badly of the Academy that it would have been very singular or very magnanimous on his part to admit him into its ranks." And so Decreux, an irascible, if successful, outsider—decided to take part in a new form of art production.

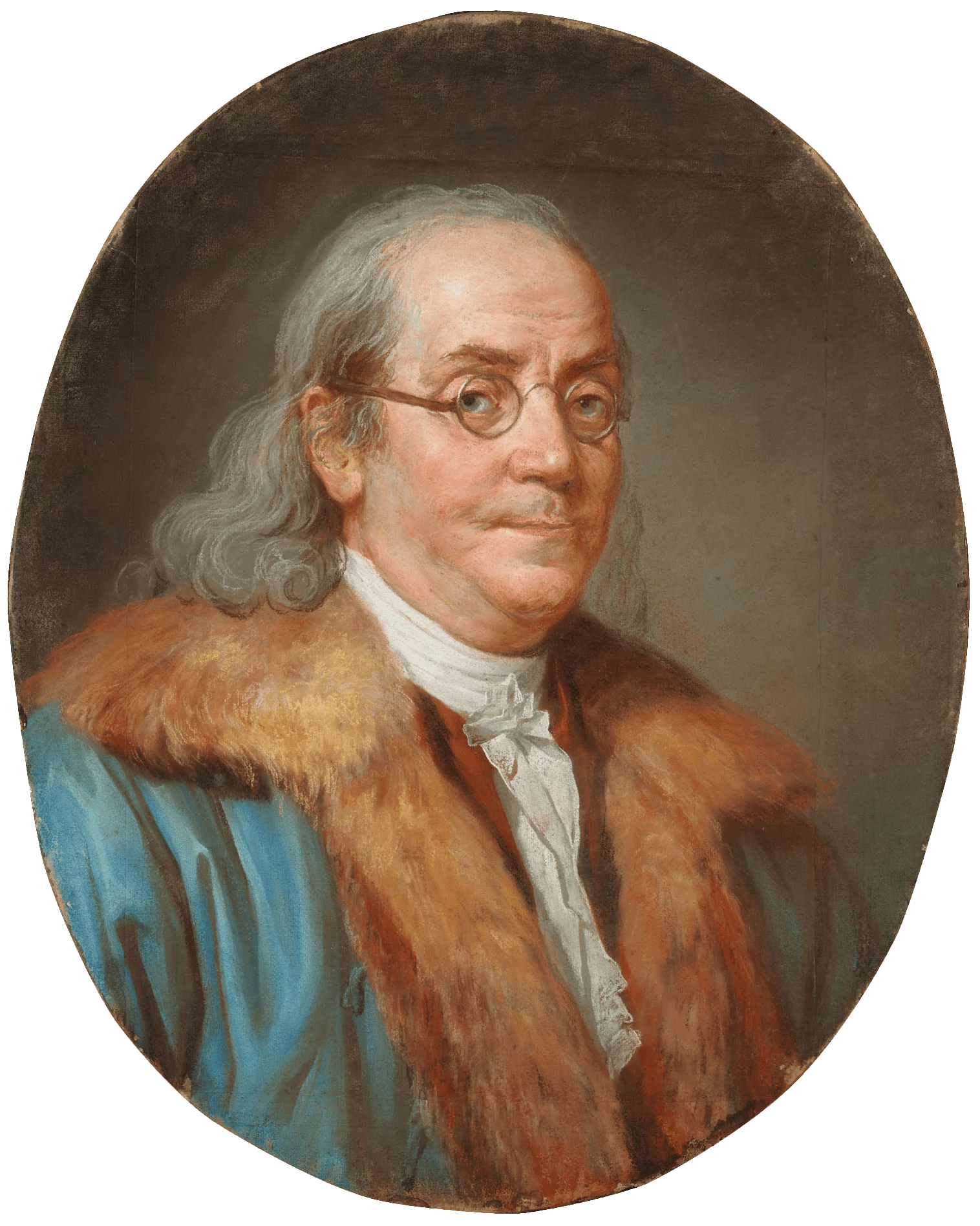

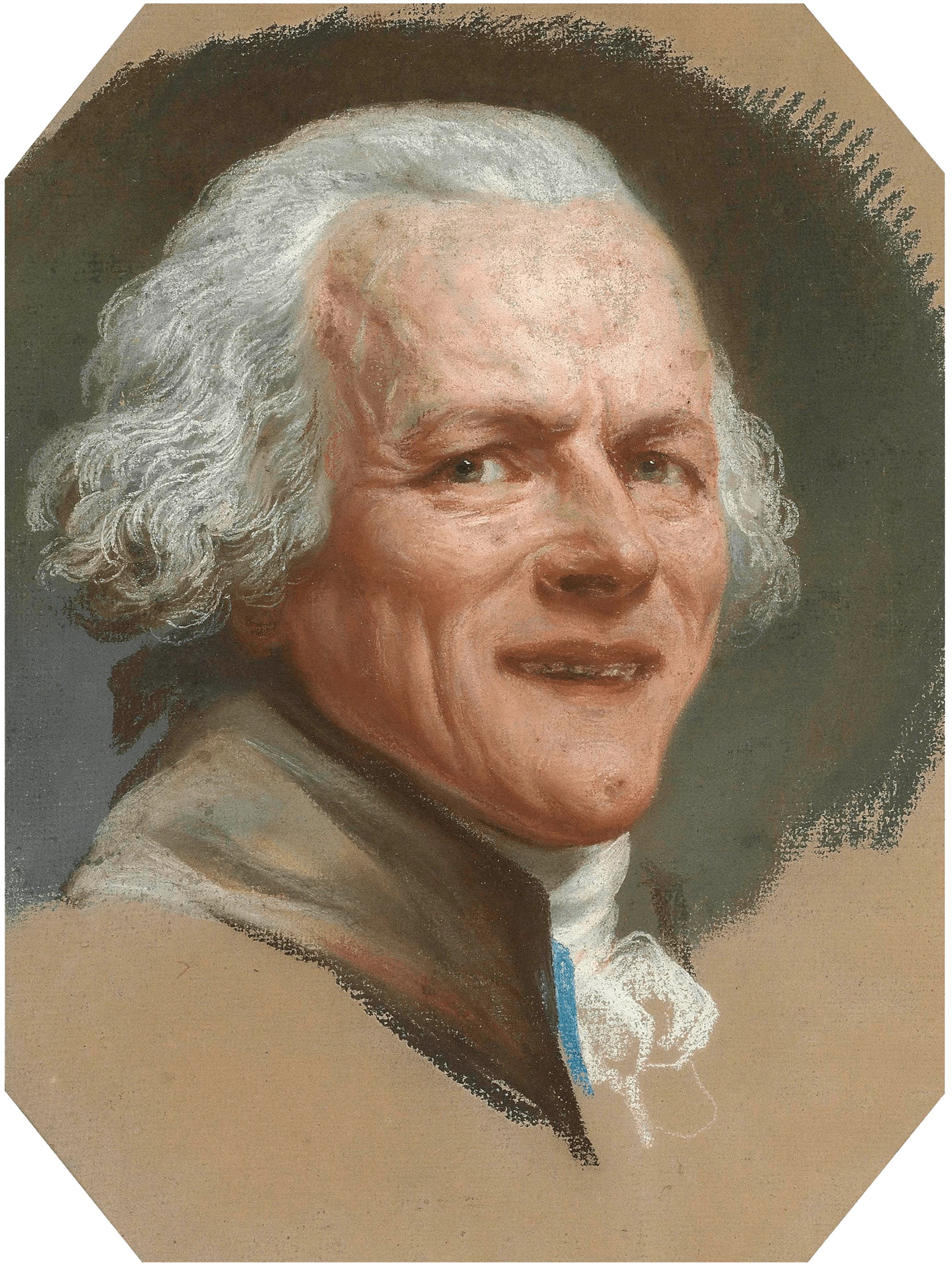

The Salon de la Correspondance was developed by the writer Pahin de La Blancherie, and consisted of a free art newspaper, printed with the support of donating patrons, and delivered, for free, to anyone who was interested. An extremely cool idea, and remarkable for a time when the state-sponsored Royal Academy dominated every aspect of French art. The Salon de la Correspondance was a populist undertaking, and Decreux was on board. His first contribution, in 1781, was a portrait of its founder La Blancherie. The next year, he submitted a portrait of Benjamin Franklin described as "the portrait of a man always seen with enthusiasm is painted here in a scholarly and bold manner." And finally, on December 10, 1783, the salon published the first glimpse of the Ducreux we know and love today, "a man dressed in red in the attitude of yawning." Unbound from the expectations of a wealthy client and the judgements of the Royal Academy, Ducreux leaned into expression, let himself have some fun. 240 years later, this portrait is unlike anything else. Rather than preserving a subject at their best, he captured a candid moment of surprising vulnerability. This radical shift in portraiture became his signature—a meme during his own life, for better or worse.

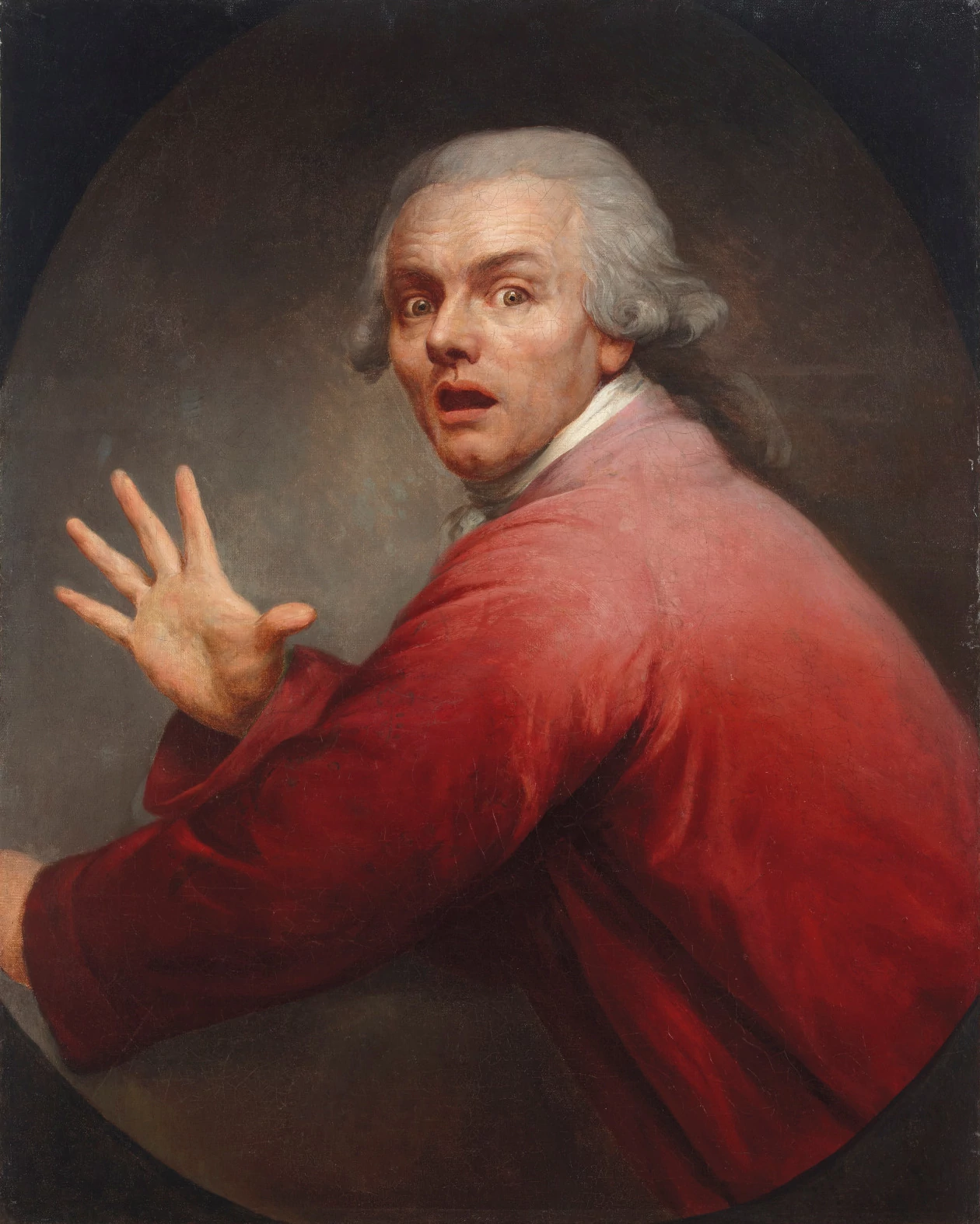

In 1791, Ducreux had fled the violence of the budding French Revolution and was living in London. Without his network of clients, he turned to the Royal Academy of London, where he showed five paintings, including "The Surprise in Terror." He prepared engravings to sell accompanying the show, including Le Rieur, Le Joueur éploré, and an engraved version of "Le Discret" which garnered little praise and less money. Ducreux returned to Paris, despite the unrest to participate in a show at the Louvre, this time, side by side with his daughter Rose, now a successful painter in her own right. He exhibited his yawning man from the Salon de la correspondence, and recontextualized within the hallowed halls it was received with jeers. Voltaire's Crutch writes: “Well! Was I wrong to say that M. Ducreux made you yawn wonderfully?" Another critic, "he is one of those ordinary talents which tends more towards mediocrity than towards perfection" and another, "strong wooden heads, a yawner to make the lackeys laugh."

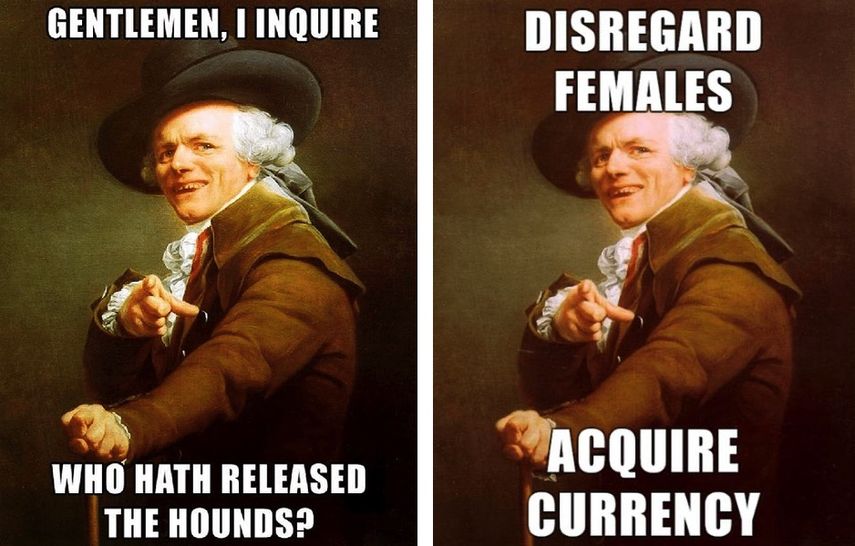

In 1793, Marie Antoinette Josèphe Jeanne was beheaded by guillotine. We don't know how Ducreux felt, losing the patron that elevated him from the rank and file, but it's likely he was preoccupied with survival. It's a confusing and poorly documented period for Ducreux, in January he'd painted a portrait of Louis XVI, later that year he showed a portrait of Robespierre in the Salon. In a move either tone-deaf or absolutely buck wild, the 1793 salon also featured the work that has carried Ducreux into the contemporary meme-scape. Its registry lists it as "A mockingbird pointing. 3 feet 2 inches high by 2 and a half feet wide" and reviewed as “Expressive, but charged; one neck dirty, the right hand too small, the other unhappy.”

The next few years were hard for Ducreux and his two sons and two daughters. The new Republic intended to house artists in the Louvre, and Ducreux was forced to negotiate for months to stay in the home that they had rented for many years in Paris. In a tragic and impassioned letter to the state, Decruex begs to remain in their home by appealing to his loyalty to the French republic and calling out his expressive self portraits as revolutionary statements:

"I myself have since forgotten my palette and my brushes; the civil functions entrusted to me by my section occupied me completely; I was commissary of police in the Paris camp. I am criticized for being a portrait painter, but national benevolence must be as vast as genius and must not exclude any genre in the arts. Besides, those who have seen the Mocker, the Silence and the Mocker at the salon, paintings of character which prove that certain portrait painters can paint history."

While they avoided a poorly-planned relocation that would have required the family to eat, sleep, cook, and wash in communal spaces while tiptoeing around ancient sculpture, in 1799 their home was claimed by the state, reshuffled by the inspector of the Palace of Sciences and Arts. They were granted 'temporary accommodation' in another building, forcing Ducreux to beg for the state's assistance on April 30, 1799, writing "The impossibility in which I am of being able to do this, having had no work for three years, forces me to make this request of you. You forced an unhappy family."

Ducreux's last salon was the Salon of the year IX, in 1801. He showed portraits of the author Lantier, Madame Hamot, Cousin-Jacques, Rear Admiral Lacrosse, General of Division Clarke, and it was a devastating show. Of the general the review said "Let Ducreux return to pastel, which he handles, it is said, much better, but here this brush is an enemy, the general is mistreated, this head is raw and red, those evil hands. The body does not turn, it is not painted, why this balustrade by the sea? Why this idle look. It is not representing one of our soldiers as they should be and as they are.” Of Jacques, "We do not know precisely in which world our dear cousin has painted; his portrait is thought to be the masterpiece of a lunar painter, because, we are told, in the moon the arts are still in their cradle."

After his rough showing at Salon IX, Decreux was preparing for the next year's salon when he collapsed on the road to Saint-Denis while walking to visit his friend Mr. Hamot. In the obituary of the “Journal des Débats” it was written “Citizen Ducreux, painter of pastel portraits, has just died suddenly and in a rather unfortunate way. He was walking to the country house of one of his friends, near Saint-Denis. In the main avenue he found himself indisposed, he called to his aid a passing soldier; but he was fatally struck in less than 3 minutes he expired in his arms. Taken to Saint-Denis, we have seen his profession and his residence by his papers. Citizen Ducreux died in his sixty-fourth year, he had achieved success in the genre of painting he had adopted.”

A painter of portraits that changed the political landscape of countries, or self-portraits that changed what it means to be seen, died in a ditch of a presumed stroke "a burst of blood or of some crack in some large blood vessels." As his biographer put it, "As we have seen, the last years of Ducreux's life had been darkened by deep sorrow."

In November of 2009, a snarky internet-dweller kicked off an unexpected revival of Ducreux, thanks to the memeification of his Mockingbird self-portrait, captioned with a quote from Notorious B.I.G’s 1995 Get Money, “fuck bitches, get money" rewritten in archaic pastish: “Disregard Females, Acquire Currency.” I suspect that Ducreux would appreciate the appropriation, after all, his expressive portraits were first shown in a revolutionary direct-to-audience format outside of the academic art world. From the Salon de la Correspondance to the Reddit Meme boards isn't much of a stretch, and while steeped in the fear and uncertainty of revolutionary France Ducreux stayed true to his weird, subversive self-portraits, the fact he was resurrected to bring image macro levity to an uncertain world once again, just feels right.

...

Note from the author: This bio is much longer than my usual essays, because I wanted to take full advantage of some unusual source material. If you've looked into Ducreux before, you've probably noticed that there's not a lot of info on the guy, in English. Turns out, there's an out-of-print biography of Ducreux written by Georgette Lyon, that's never been translated from its original French. I picked up a well-loved copy, scanned and OCRed it, and ran the whole mess through Google Translate. The result was expectedly imperfect, but the information that appeared I've not found anywhere else online, and I feel strangely privileged to share it. If you've taken the time to read this, thank you, and if you like content like this, please consider supporting Obelisk on Patreon. Your monthly contributions go directly to sourcing weird, rare, often out of print books on artists who've gotten largely skipped over by the contemporary canon, allowing me to develop and share new perspectives on art history. Thanks and much love,

—Reed

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about Joseph Ducreux? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.