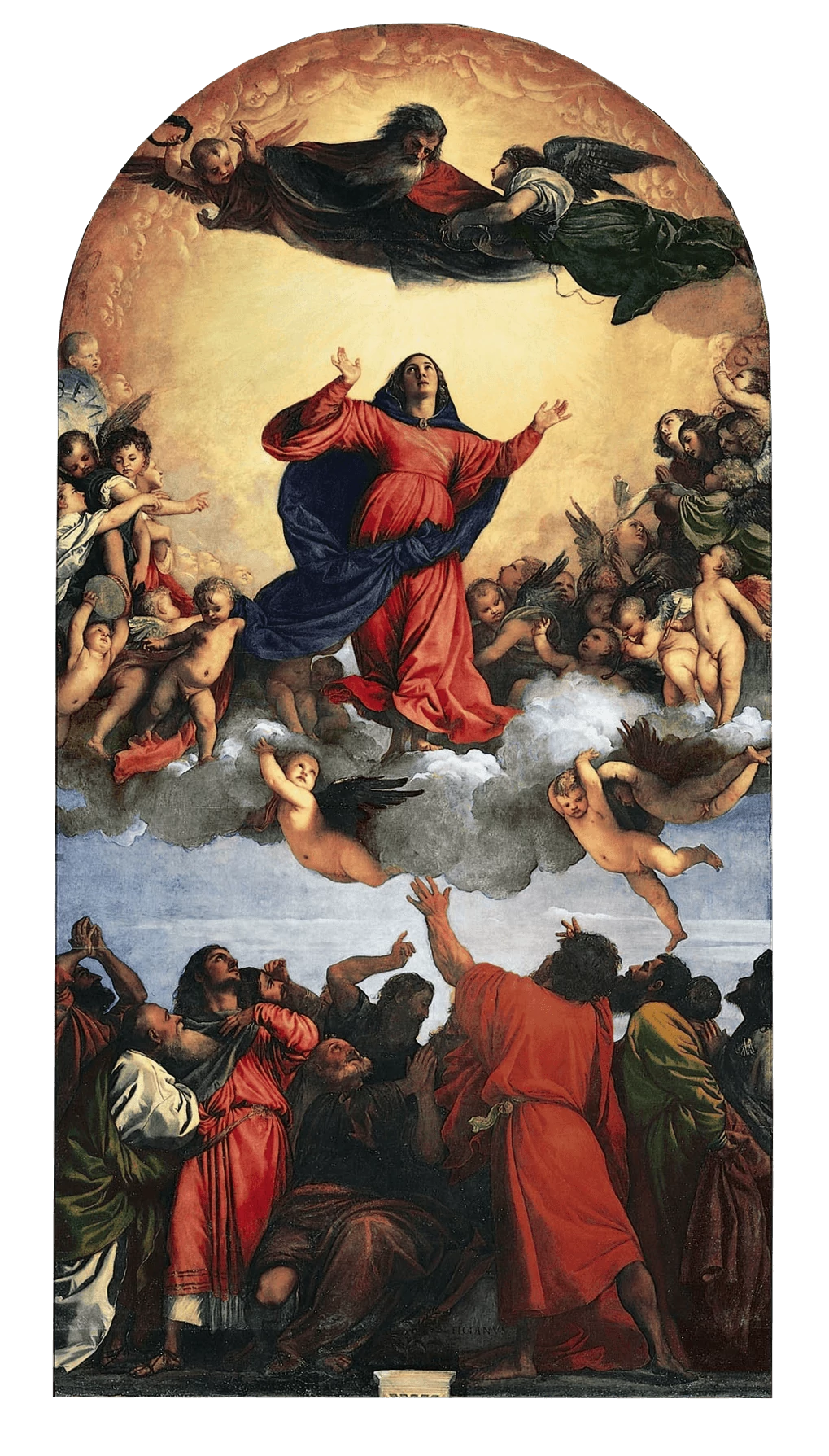

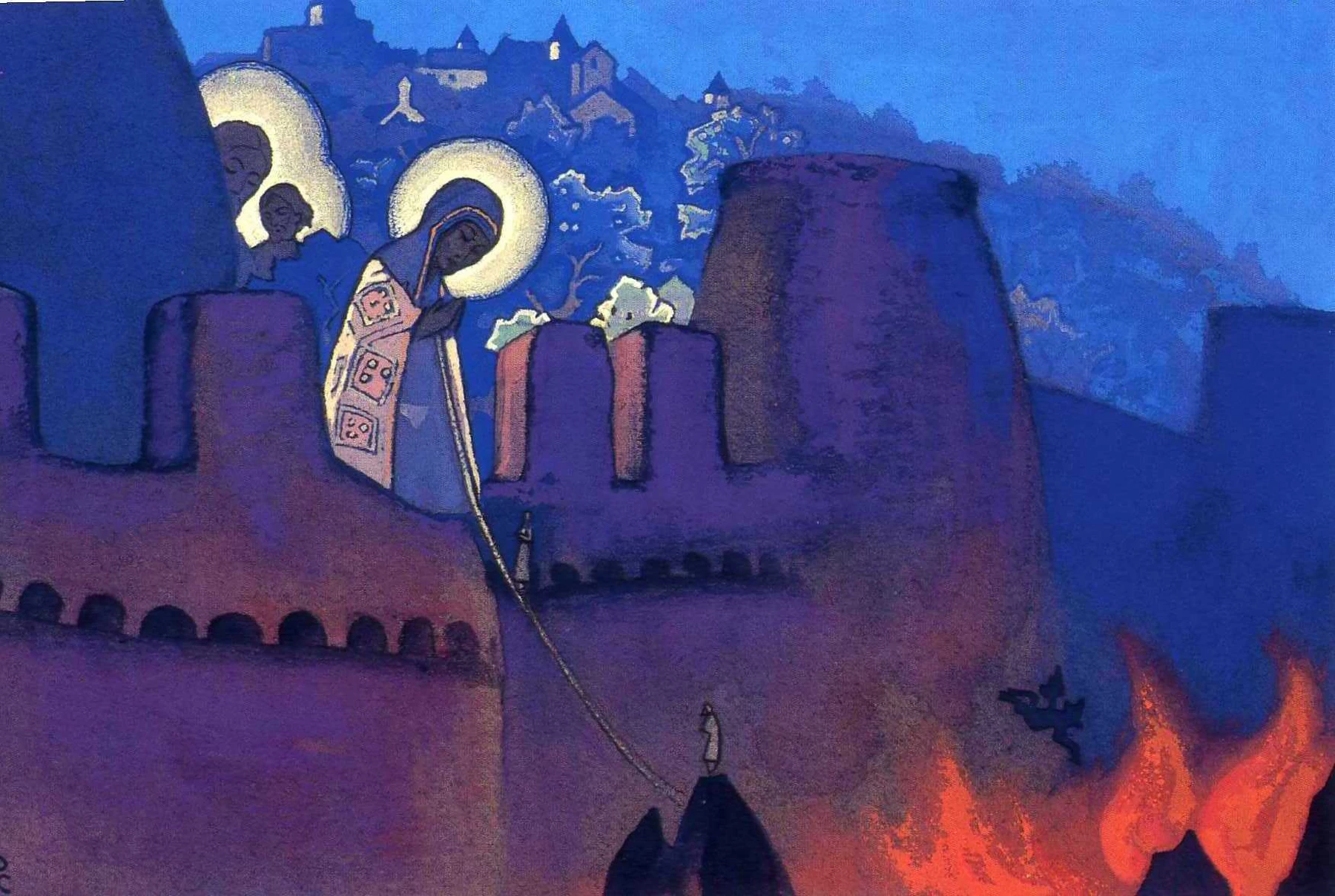

The Virgin Mary, or the Madonna, is one of the most popular tropes in Western religious art. Since 431 CE, when a council of Christian bishops met in Ephesus and canonized Mary as Theotokos, or the God-bearer, her holy figure has been used to represent a wide range of virtues. The singular madonna may gesture benediction & prayer on behalf of humanity, the madonna and child shows humanity’s embrace of the holy son, the Madonnas of humility sit on the ground to display their humble piety, the adoring madonna kneels at the foot of the christ-child. Madonna Lactans breastfeed the young Jesus to impart wisdom, the Virgin Hodegetria points out Christ’s divinity to humanity, Annunciations show Mary visited by an angel announcing her virgin conception, Assumptions of the Virgin show Mary ascending, often alive, to heaven, and the Black Madonnas depict a dark-skinned Mary, connecting to syncretic or cross-cultural faiths in the maternal divine.

Let’s talk about cults. The Council of Ephesus had a lot on their plate when it came to the Virgin Mary. Until the year 431, Nestorius, the Archbishop of Constantinople, held that Mary could be called Christotokos, or Christ-bearer but not God-bearer, reflecting his belief that Christ was not a singular being, but divinity and humanity trapped in the same body. This went over poorly with the 250 bishops summoned to Ephesus, and Nestorius was charged with heresy and deposed, and the unexpected result of this orthodox drama was the canonization of the so-called Cult of Mary.

Cults, in the historical sense, were not personality-driven fringe religious movements with a taste for Kool Aid, they were, as Roman philosopher Cicero described them cultus deorum—the “cultivation of the gods” or “giving the gods their due.” The Cult of Mary, then, was the religious practice of her veneration, and by defining Mary as “God-bearer” the Council changed worship of Mary from idolatry to glorification of a divine mother. The rest, as they say, is 1600 years of history.

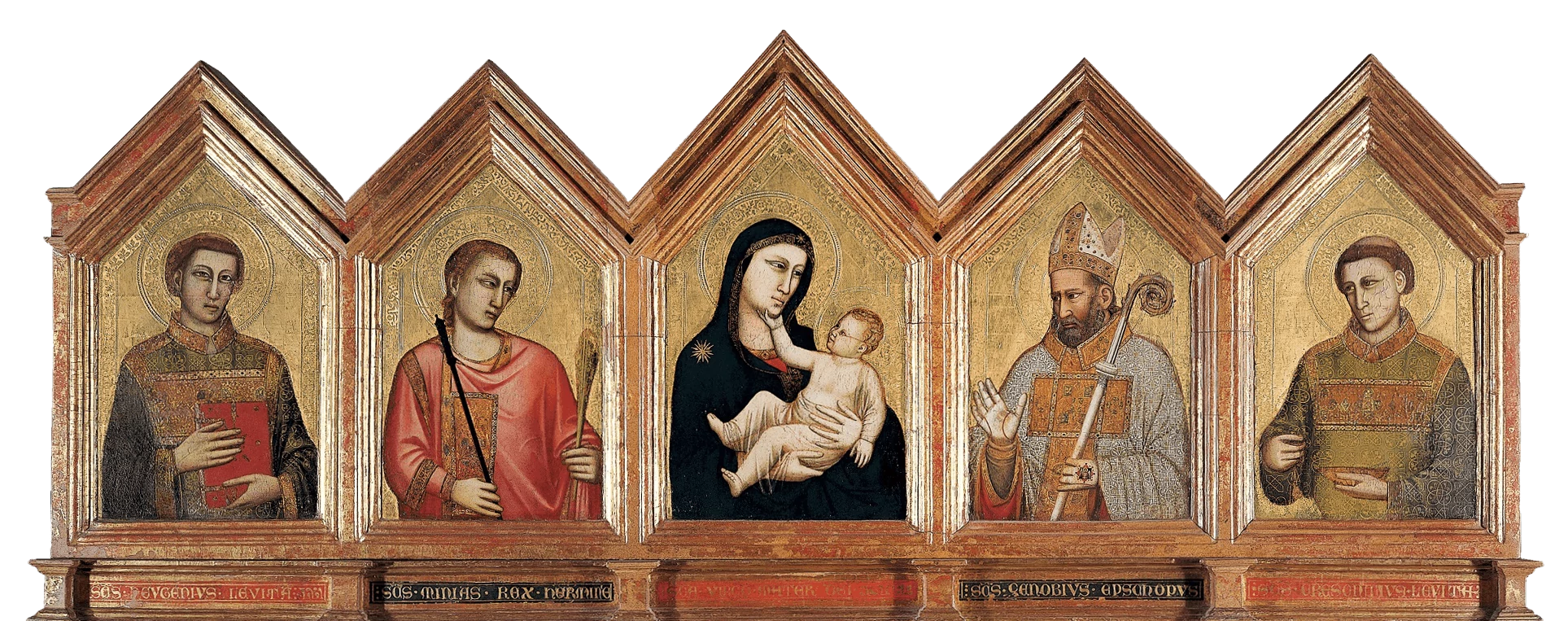

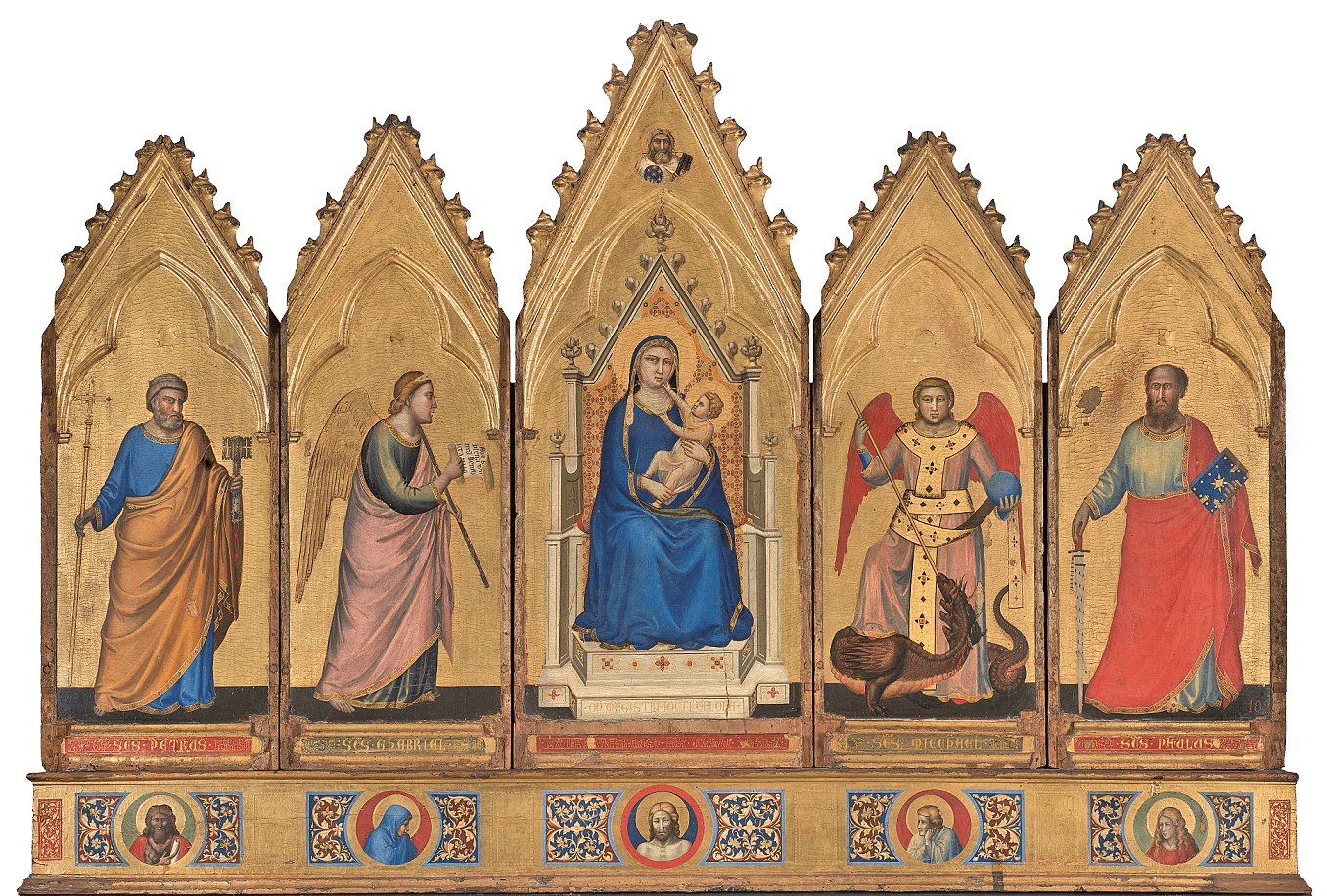

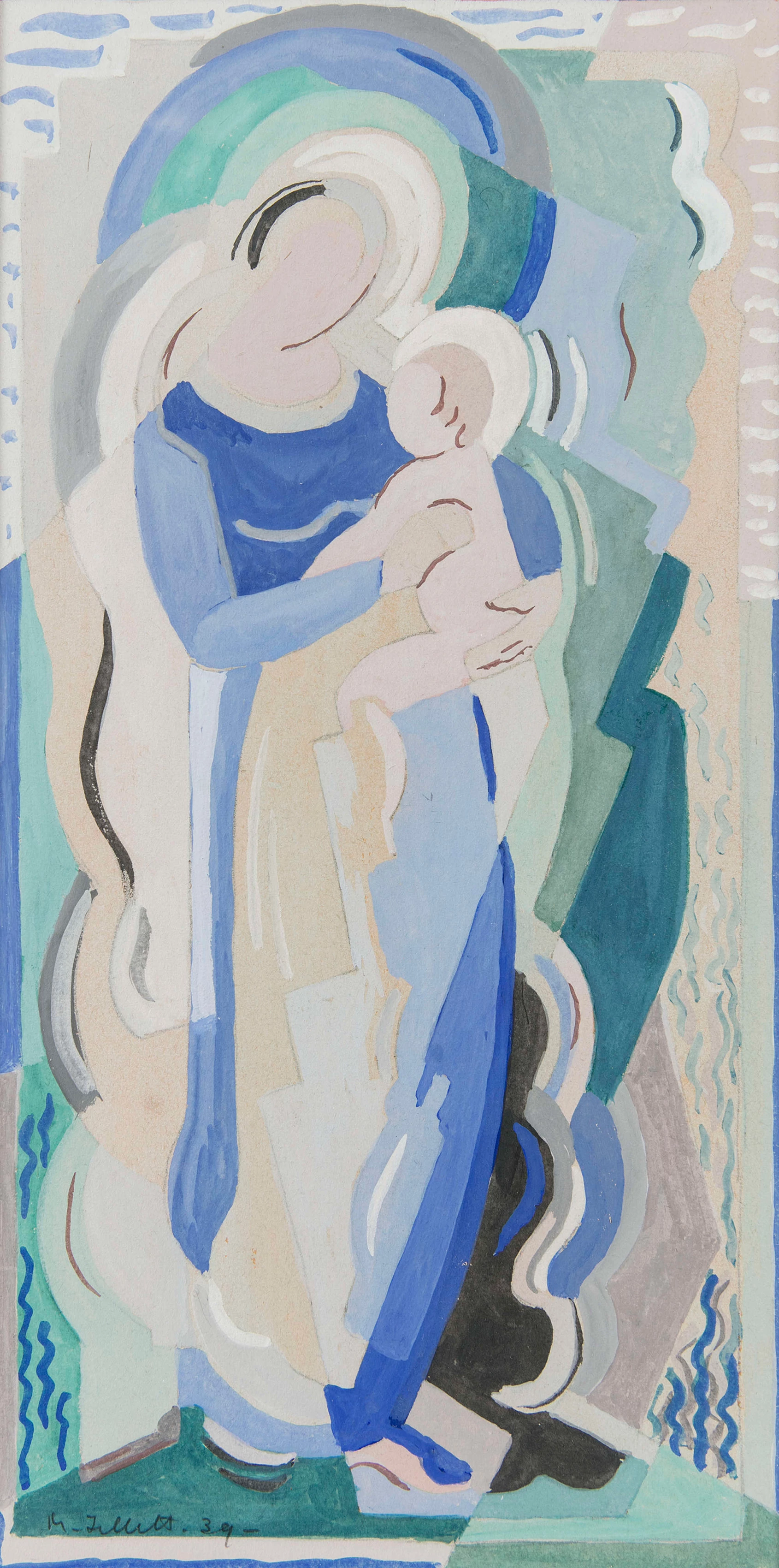

As one of the longest-standing figures in Western Art, it’s fun to watch the Virgin Mary evolve over time. She’s a fluid character, embodying both the somber faith of the Gothic era in Carlo Crivelli’s insouciant Madonna and Child Enthroned, and the warmth and humanism of the Italian Renaissance in Giampietrino’s Madonna and Child. And the modern era takes Mary even further. She is transformed into a vampiric temptress by Edvard Munch, a faceless every-mother by Mainie Jellett, a degenerate nightmare by Alice Neel, and by Henry Ossawa Tanner, back to the form she must have had more than two millennia ago—a young, confused girl, by herself.

When looking at these many, many madonnas, I find it interesting to take note of whether the artist is a man or a woman. With notable exceptions, like Tanner, male artists approach Mary as an icon, an archetype. Virtuous maiden, stately matron, grieving mother, ocassionally femme fatal. She is what her role proscribes her to be. Women artists, one the other hand, capture over and over again the humanness of the character. Elisabetta Sirani’s serene Mary is the cover of this article. Julia Margaret Cameron discovers both the beauty and the exhausting, constant labor of motherhood in the remarkable photograph Madonna with Children. Marianne Stokes depicts the new mother lost in a much-needed nap, and Barbara Longhi gives the ever-patient woman a book to read during her centuries-long modeling session.

...

Got questions, comments or corrections about The Virgin Mary? Join the conversation in our Discord, and if you enjoy content like this, consider becoming a member for exclusive essays, downloadables, and discounts in the Obelisk Store.